It’s exactly 50 years since a dreadful accident in the Dutch Grand Prix shamed Formula One and, perhaps, robbed Britain of its next World Champion.

At the time, several young British chargers were being eyed by F1 teams: Tom Pryce, Tony Brise and James Hunt all looked like strong hopes for the future.

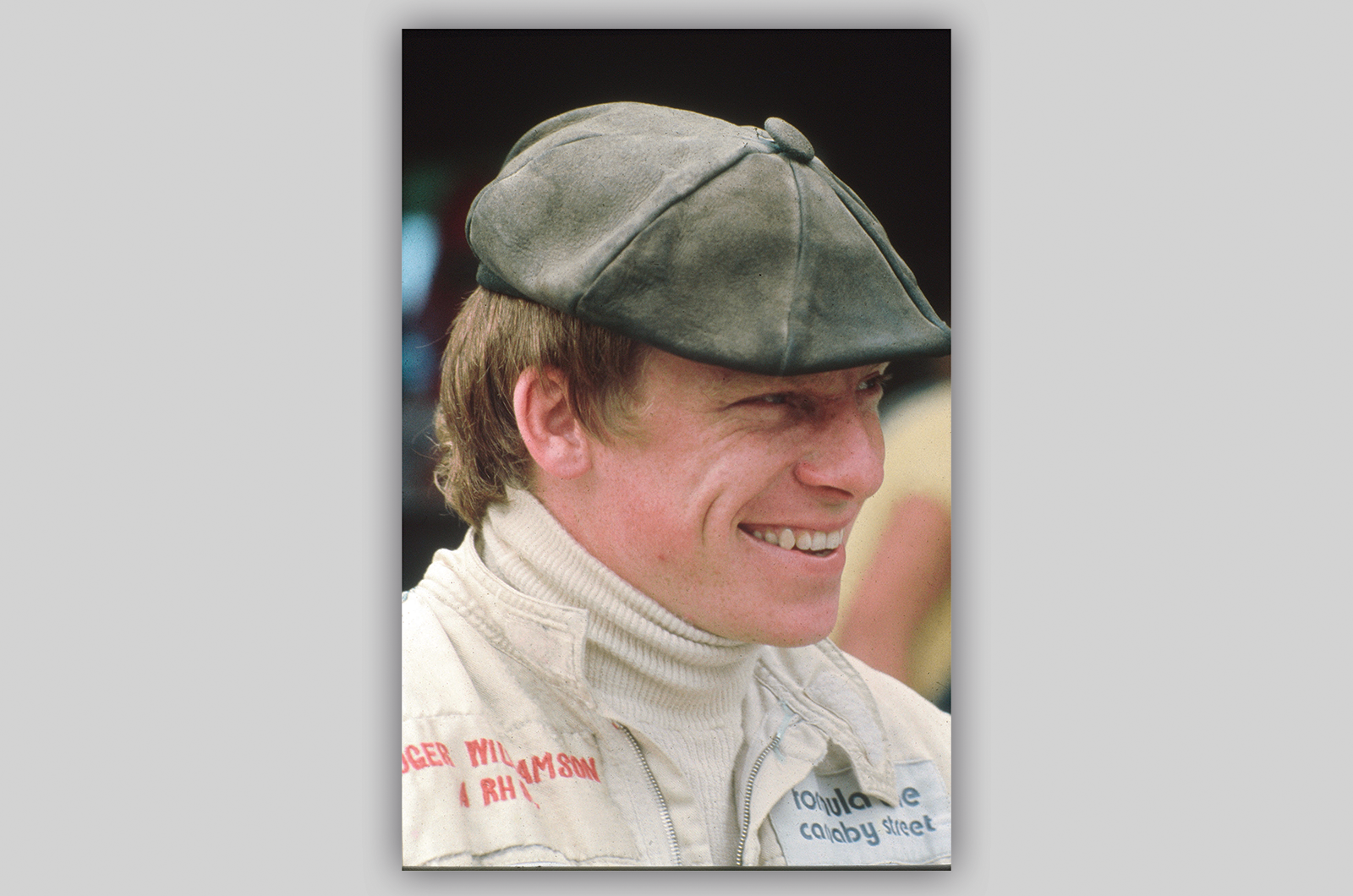

But for many the man on his way to the top was a stocky, smiling lad from Leicester called Roger Williamson.

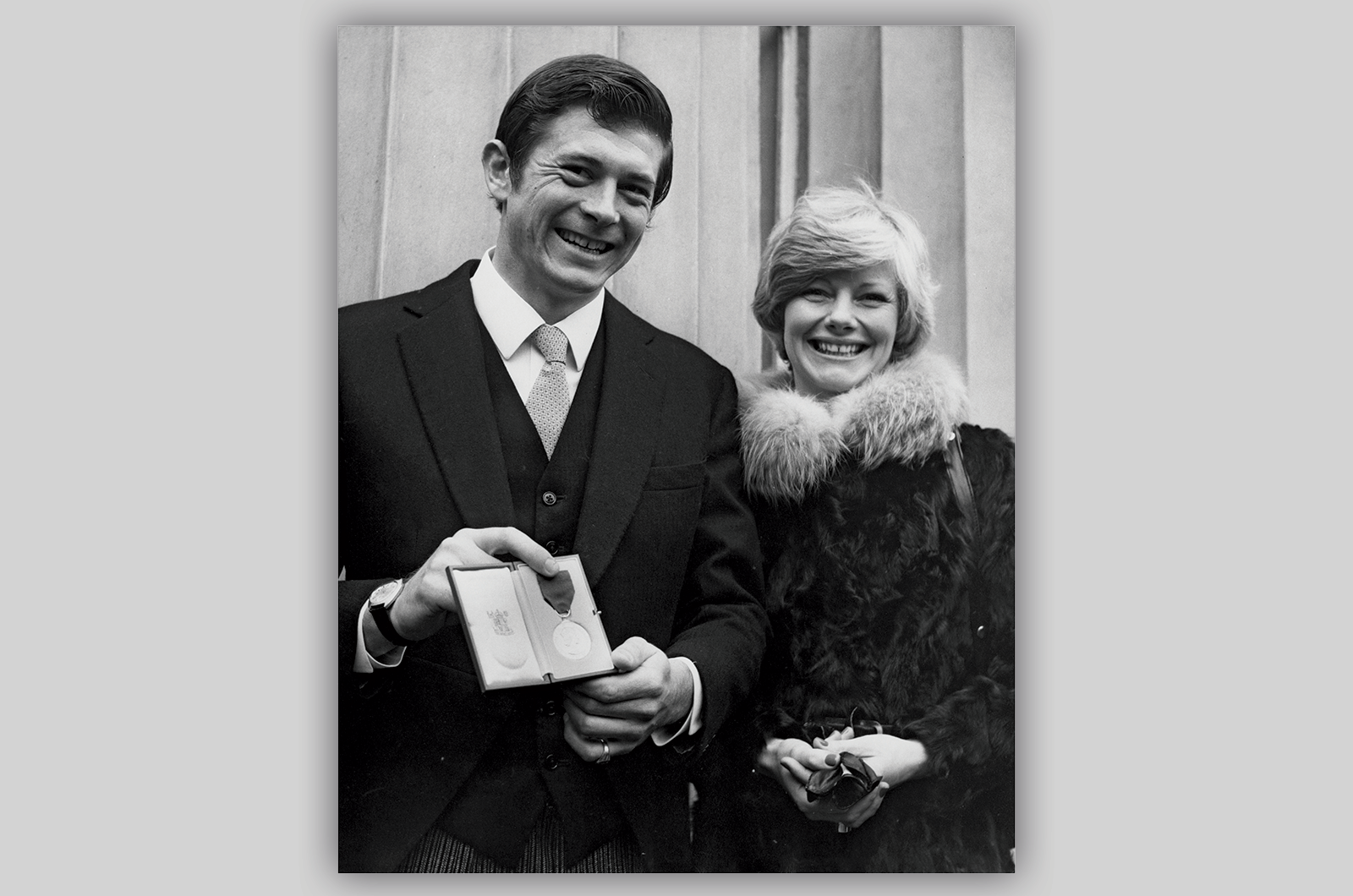

Roger Williamson (left) with his backer and friend, Tom Wheatcroft, in 1971

Roger came via boyhood karting to club racing in a self-built Mini, winning 14 out of 18 races.

He went on to dominate the 1970 club saloon championship in an indecently fast Ford Anglia.

Then his dad, Dodge, who ran a small garage and raced speedway ’bikes, scraped up the funds to buy him a Formula Three car on hire purchase.

At once he was winning, but Dodge still hadn’t made the first payment when the tired engine needed an urgent rebuild.

In the paddock, a thickset chap with a broad Leicester accent came up and said: “Why don’t you put in yer spare engine?”

Roger laughed: “What spare engine?” So the man said: “Go and buy one, lad. I’ll pay fer it.”