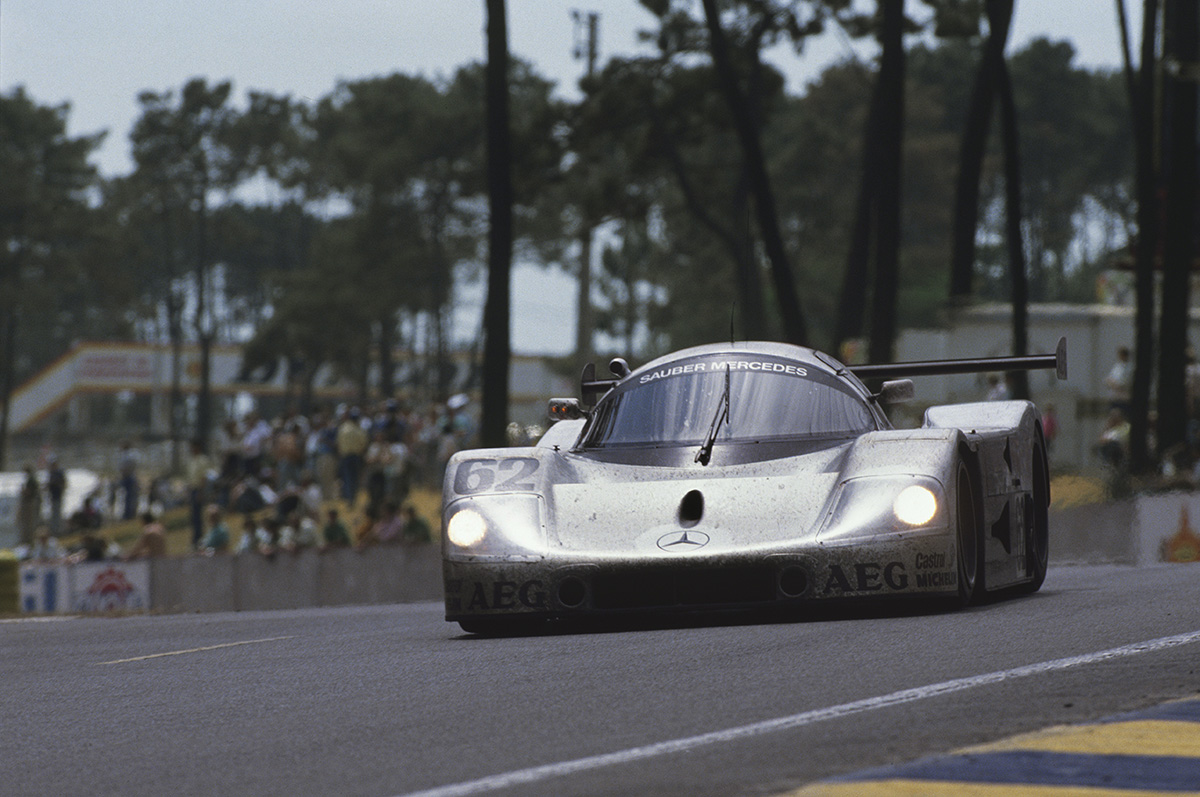

Sportscar racing suffered one of its occasional dips in mid- to late-1970s, yet the arrival of the Group C formula in 1982 sparked a glorious revival. At its heart were minimum-weight (800kg) and fuel-efficiency regulations that enabled the likes of the normally aspirated V12 Jaguars to take on the turbocharged Porsches. Other manufacturers joined in, too, from Mercedes and Lancia to Japanese powerhouses Nissan and Toyota.

With countless privateers bolstering grids around the world, the result was some of the most enthralling and memorable racing ever seen, with the Jaguar vs Porsche vs Mercedes battles creating a storyline that rivalled anything Formula One could offer.

These spectacular cars are now enjoying a second lease of life in historics racing, and they are set to return to their spiritual home for what should be an unforgettable outing at this year’s Le Mans Classic (8-10 July).

Built as a replacement for the Group 6 936, the 956 set the standard during the early days of the Group C formula. It featured Porsche’s first monocoque (constructed in aluminium), as well as ground-effect aerodynamics and a 2.65-litre turbocharged flat-six that offered in excess of 635bhp.

Such was the car’s dominance that the factory entries scored a 1-2-3 at La Sarthe at their first attempt, with Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell taking the top honours ahead of Jochen Mass/Very Schuppan and the third-placed Al Holbert/Hurley Haywood/Jürgen Barth.

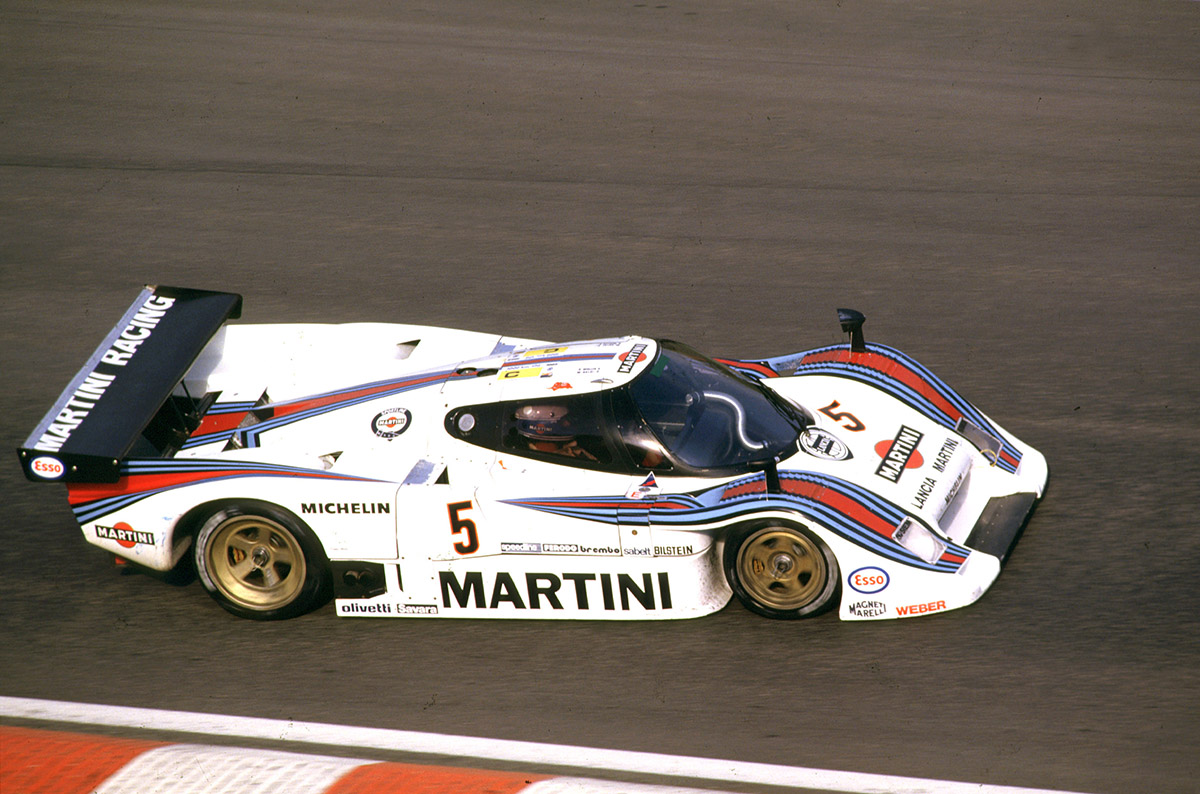

Like Porsche, Lancia were early converts to Group C, developing their LC2 as a replacement for the open-cockpit Group 6 LC1. Powered by a modified version of Ferrari’s four-valve V8 engine, there was no doubting the LC2’s pace. In fact, the Martini-liveried car of Bob Wollek and Alessandra Nannini qualified on pole position at Le Mans in 1984, a full 11 seconds quicker than the winning Porsche.