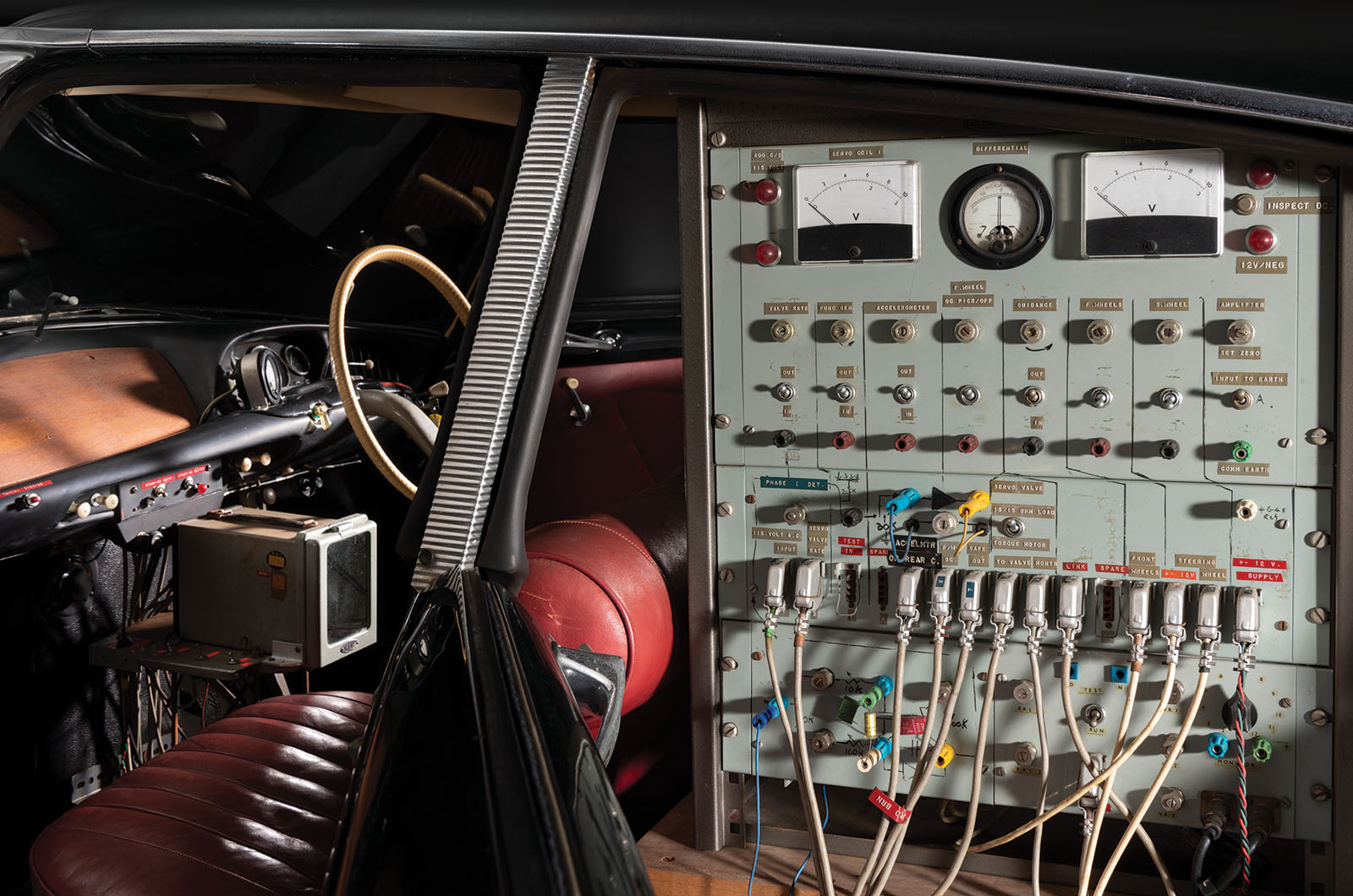

“We have a few other items from them,” says Heather, “mainly measuring equipment from different tests.”

But why get rid of YXU 845? “It was to do with funding,” she says. “They proved the system was effective with one car, but being able to scale it up and ensure it was reliable and safe would be very costly; putting the infrastructure in place would be even more. I think it just wasn’t a priority at the time.”

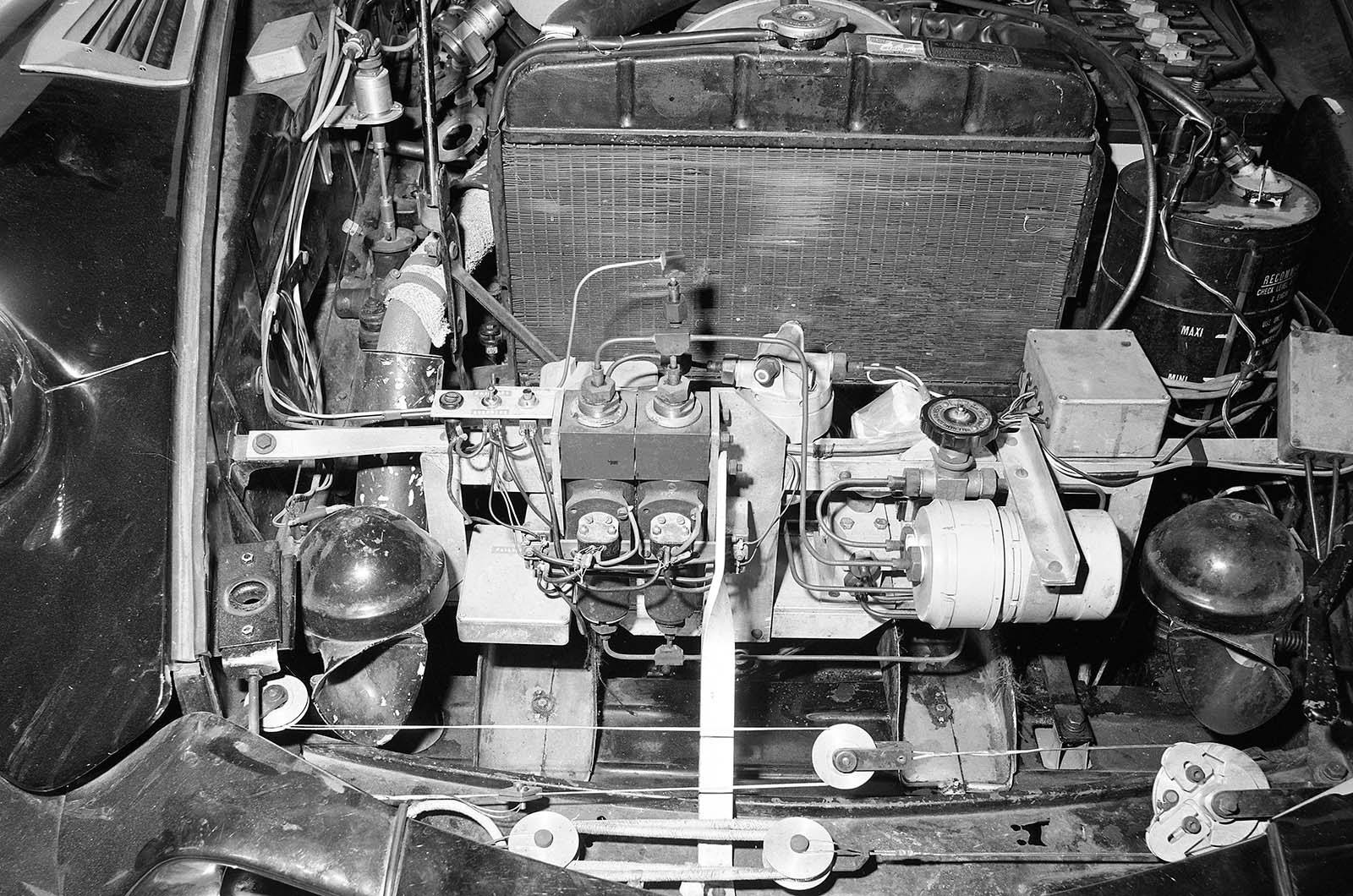

The Road Research Laboratory’s Citroën DS was a self-driving car built in Britain a decade before Elon Musk was born

Similar projects continued in the ’70s with a modified Ford Cortina and a Mini, but progress petered out as the RRL focused on other projects (see below).

Perhaps the road to automation was not as straightforward as it first seemed?

Public acceptance, legislation and moral conundrums about the decisions a car should be allowed to make are some of the barriers facing self-driving technology companies today.

The RRL, now the Transport Research Laboratory, didn’t return to self-driving vehicle trials until its GATEway Project in 2015, when four autonomous pods were let loose in the capital.

“They proved the system was effective with one car, but being able to scale it up and ensure it was reliable and safe would be very costly”

Are we asking too much of the tech? Maybe they don’t need to be in control 100% of the time.

The mind-boggling algorithms and game-changing Lidar sensors are impressive, but, in our quest for automation, perhaps we have overlooked the relatively simple solution developed by the RRL in the 1960s.

Either way, Silicon Valley rules the roost when it comes to self-driving technology in the 21st century, but it’s nice to know that much of the groundwork was laid by a team of scientists and engineers in Berkshire, England, some 60 years ago.

Images: Science Museum/Transport Research Laboratory

Thanks to: Science Museum; Transport Research Laboratory; Hannah Fry’s book, Hello World (ISBN 9780857525246)

More Road Research Laboratory experiments

Cars were once tested at up to 155mph on the banked circuit. Today, pedestrian traffic passes at a more sedate pace

The Road Research Laboratory was established in 1933, when the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research took over from the Road Experimental Station in Harmondsworth, London.

Initially, its main job was to advise the government on what materials and methods to use for its rapidly expanding network of highways.

After helping the Ministry of Aircraft Production and other departments during WW2 (investigating methods to speed up the construction of runways and testing the bouncing bomb for the Dambusters raid were among its wartime jobs), it was given the responsibility to study other areas of road safety in the 1940s and ’50s.

In 1966, the RRL moved its headquarters to the Crowthorne proving ground in Berkshire.

The fire tower doubled as a vantage point for experiments on The Pan

It conducted a huge variety of trials, from experiments with early sat-navs to creating an inhibitor that could be added to road de-icing salts to reduce vehicle corrosion.

The latter involved ordering a batch of seven ADO16 saloons from BMC and then driving them through shallow pools of water.

Some cars were driven into a pool of rainwater, others went through salty water, and the rest forded salted water mixed with the new inhibitor.

When signs of corrosion began to show, the cars were cut open and assessed.

Road Research Laboratory trials included this heated road, which was installed in Slough

The RRL helped pioneer vehicle safety innovations throughout the 20th century, analysing rear-view mirrors, anti-lock brakes, deformable front bumpers and more.

“Take your pick,” says Penny While, head of marketing and unofficial archivist at the Transport Research Laboratory (as the organisation was renamed when it became an executive agency of the Department of Transport in 1992, shortly before it was privatised in ’96).

“The TRL takes other people’s ideas and road tests them to find out if they are viable and helpful.

“Seatbelts were not an RRL invention, but it led the way in devising the test standards for their use and persuaded car makers to adopt the three-point system.

“Anything that helps keep the traffic flowing smoothly and safely, and reduces maintenance costs, is up for investigation.”

The Road Research Laboratory’s work led to the ‘give way to traffic from right’ rule when joining a roundabout

“The RRL also co-developed crash-test dummies when it became unethical to use cadavers,” she continues.

“Some of the stranger things the lab has tested include heated roads, electric snowploughs and asphalt made of recycled water bottles.”

It also created what became the European New Car Assessment Programme (Euro NCAP).

Today, the TRL still has its headquarters in Crowthorne, but it gave up the adjacent test facility in 2015.

Some of the old site has been used to build new houses, but part of it remains as Buckler’s Forest, a nature reserve that’s open to the public.

The Small Roads Test Track replicated urban routes

Wandering around the area, you can still find traces of the RRL’s projects.

The huge fire tower – now a home for birds and bats – is perhaps the most obvious; it once overlooked some of the large-scale trials conducted on The Pan.

In 1967, thousands of cones were laid out to create a makeshift road network on the concrete expanse.

Nearly 200 vehicles were involved in the test to find out how traffic lights impacted traffic jams.

Drivers were paid five shillings an hour to take part.

The Transport Research Laboratory’s Buckler’s Forest test facility closed in 2015

From the tower, you can follow the same track where the self-steering Citroën DS proved its mettle in the ’60s, before arriving at the banked curve that’s now being reclaimed by nature.

From there, you can venture deeper into the pine trees to find the Small Roads Test Track.

Designed to resemble side streets and urban areas, there’s a cluster of road markings, traffic signs, cat’s-eye reflectors and more.

The RRL wasn’t just concerned about a vehicle’s occupants: it investigated pedestrian safety, too.

In the late 1940s, it was tasked with finding the best way to make road crossings safer and more visible.

Hill Start Hill – now a picnic spot at Buckler’s Forest nature reserve

The researchers trialled various markings, but the black-and-white zebra pattern performed best.

Little surprise that the UK’s first-ever zebra crossing appeared in 1951 on Slough High Street, not too far from the RRL’s base.

Heading back towards The Pan, you can take a rest on Hill Start Hill.

The 1-in-6 gradient slope used to be a challenge for vehicle handbrakes, but now it’s a great picnic spot for when you’ve finished the 2.2-mile walk around Buckler’s Forest.

Images: Chris Gage/Transport Research Laboratory

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

40 alternatively fuelled classic cars

Back to the future: why the Tesla Roadster is the first true electric classic car of the modern era

Bossaert GT 19: the last, forgotten Citroën DS sports coupé

Ryan Standen

Ryan Standen is Classic & Sports Car’s Editorial Assistant