-

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway -

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

© Indianapolis Motor Speedway

-

Wacky machines from the USA’s greatest race

Prestigious as the Indy 500 is, not every entrant has been a shining example of top-end engineering.

See, before the days of tight regulations and spec chassis, all sorts of oddball entries could be found doing the rounds of the Brickyard – from turbine-powered single-seaters to racers inspired by aeroplanes.

Ahead of Sunday’s 103rd running of The Greatest Spectacle in Racing, as it is known, here are 10 of the strangest machines ever to have entered the event.

-

10. Cooper Climax

First up is a car that's strange not by design, but by context: when American racer Rodger Ward entered a midget car in the 1959 US Grand Prix, he suggested to John Cooper and Jack Brabham that they should do the same at Indianapolis.

Taken with the idea, the team tested at the Speedway in late 1960 (while in the States for that year’s US Grand Prix), before entering a Cooper Climax in the following year’s 500.

-

10. Cooper Climax (cont.)

Designed for Grand Prix racing, the Cooper was fitted with a 2.7-litre version of the Coventry-Climax engine.

Despite lacking the straight line speed of its 4.2-litre Indy competitors, ‘Black Jack’ had enough grip to qualify the diminutive machine in 17th at 145mph.

He ran as high as third before finally finishing in ninth – and on the lead lap, too. We can only wonder what would happen if you entered a modern F1 car in this year's 500…

-

9. Fageol Twin Coach Special

Next up is a machine that took Indy's potential for publicity to extremes.

Having succeeded his father as president of the Fageol Twin Coach Company – a firm that made twin-engined buses – Lou Fageol decided his company would design an Indy car which, naturally, had two engines.

Two supercharged 91cu in Offenhauser motors were attached to a Miller-Ford front-wheel-drive transaxle. One drove the front, while the other was turned around to power the rear.

-

9. Fageol Twin Coach Special (cont.)

Clearly a man of some fortitude, driver Paul Russo managed to qualify the car second, but on lap 16 he hit a patch of oil and slid into the wall, breaking his leg.

The twin-engine machine would make one last appearance at Indy in 1948, driven by Bill Cantrell, while Fageol went on to compete in road events at the wheel of a similarly twin-engined Porsche 550, before becoming a well-known hydroplane racer.

-

8. Cummins Diesel

Thought Audi's diesel racers of recent years were ground-breaking? Clessie Cummins got there decades earlier.

Cummins had served on Ray Harroun’s pitcrew when the driver won the first Indy 500 in 1911, and founded the Cummins Engine Co in 1919.

He specialised in diesels, and when organisers were struggling to assemble a full grid during the Depression, they allowed Cummins to run his overweight car as a ‘special engineering entry’ – despite the 500 being an all-petrol affair.

-

8. Cummins Diesel (cont.)

Deftly demonstrating the fuel efficiency of diesel, it became the first Indy entry in history to run the entire race non-stop – and it did so, supposedly, on just US$1.40 of “furnace oil”.

It came home in a respectable 13th place, with an average speed of 86mph and a fuel consumption of 16mpg.

Cummins would return in 1934 to test two- and four-stroke engines, then again in 1950 with the supercharged ‘Green Hornet’. In 1952, a turbodiesel Cummins qualified on pole at 138mph.

-

7. MG Liquid Suspension Special

Sticking shock absorbers from a roadgoing sedan on a race car doesn't seem like a sound plan – but that's exactly what left-field designer Joe Huffaker and BMC head Kjell Qvale did with the MG Liquid Suspension Special.

Entered into the 1964 500, it used the Hydrolastic suspension system found on the likes of the MG 1100.

-

7. MG Liquid Suspension Special (cont.)

Tested in early '64 by the legendary AJ Foyt (who would go on to win that year's 500 with Ansted-Thompson Racing), rookie Walt Hansgen went on to qualify the unique Liquid Suspension machine in 10th place at Indy, with an average speed of 153mph.

He ran as high as fourth, before retiring on lap 176 to be listed in 13th place – though the suspension had surely shown its capabilities.

-

6. Pat Clancy Special

From Auto Union in the 1930s, to Tyrrell, March and Williams in the ’70s and ’80s, manufacturers have long been playing around with the idea of six wheels on a race car – and, in 1948, Billy DeVore turned up at Indy with this, the only six-wheeler to compete in the 500.

Using the configuration later followed by March and Williams, the Kurtis chassis was modified to carry four solid Halibrand magnesium wheels at the back.

-

6. Pat Clancy Special (cont.)

The two axles were connected by a universal joint, which gave the car four-wheel drive. DeVore tested it at Arlington Downs.

“I believe that, with all four wheels driving, it will outperform conventional cars,” he said. “It certainly handles like a good race car.”

Powered by an Offenhauser engine, it was quick in a straight line but struggled in the turns. DeVore was classified 12th, and the Kurtis was later converted to a conventional four-wheeler.

-

5. Hurst Floor Shifter

Legendary mechanic and designer Henry ‘Smokey’ Yunick had a long history of off-the-wall ideas, some of which pushed the limits of what the rule-makers had in mind.

Perhaps his most bonkers creation was the 1964 Hurst Floor Shifter. Yunick came up with a design that consisted of two ‘pods’ that separated the driver and the engine, and must have made for one seriously hairy ride.

-

5. Hurst Floor Shifter (cont.)

The main body of the car contained the Offenhauser engine, while the driver – Bobby Johns, who surely qualified for some sort of bravery award – sat to the left in something resembling an exposed sidecar.

With the weight offset and the car boasting a low frontal area, you could almost understand the thinking behind it – but Johns crashed it during practice so it never ran in the 500 itself. Perhaps for the best.

-

4. Miller Gulf Special

Harry Miller’s designs dominated the 500 during the 1920s, but his efforts the following decade weren't so successful.

His final project was bought out by Gulf as Miller went bankrupt – yet the car turned out to be truly cutting edge: it had a mid-mounted 180cu in blown Miller ‘six’ motor, four-wheel drive, independent suspension, side-mounted fuel tanks and disc brakes – most of which are still seen on race cars today.

-

4. Miller Gulf Special (cont.)

It failed to qualify in 1938 following rushed preparations, but 1939 was more successful: the Miller Gulf Special became the first rear-engined car ever to qualify for the 500.

Alas, despite being sixth fastest, driver George Bailey had to retire the car after 39 laps. Miller then fell out with Gulf that summer and died in 1943, in a sad end to what had been a legendary career.

Intriguingly, when his assets were auctioned, Fred Offenhauser bought the rights to a four-cylinder engine design that would become a staple at Indy for almost 30 years

-

3. STP Paxton Turbocar

With the jet age in full swing, it was only a matter of time before adventurous (or crazy) designers tried strapping gas turbines to race cars.

Several broke cover in the '60s (including one driven by Dan Gurney in 1962), but it was the STP Paxton Turbocar that was most successful, coming within a few miles of winning the 1967 Indy 500.

Designed by Ken Wallis and backed by STP, its debut was delayed by the discovery that the aluminium frame was warping due to the intense heat of the turbine.

-

3. STP Paxton Turbocar (cont.)

Issues solved, it was entered into the 1967 500. The cockpit was positioned on the right of the backbone chassis, with the Pratt & Witney ST6 turbine to the left, with a single-speed torque converter providing drive to all four wheels.

Driver Parnelli Jones was suitably impressed when he tested it at Phoenix in early ’67 (even though the throttle took three seconds to respond).

He qualified sixth at Indy and led the race until a bearing failed with three laps to go. The rule-makers reacted immediately, with turbines soon banned.

-

2. Eagle Aircraft Flyer Special

At the height of the ground-effect era, when designers such as Colin Chapman were attempting to exploit every possible aerodynamic trait to improve downforce, short-track racer Kenny Hamilton tried to qualify a car that lacked any real aerodynamic sophistication whatsoever.

The woeful racer was designed by Dean Wilson, founder of Eagle Aircraft Company and proven aviation designer. With the backing of a millionaire, he turned his hand to penning an Indycar.

-

2. Eagle Aircraft Flyer Special (cont.)

Alas, while the car looked every bit the rocket ship – with fins and a pilot-like driving position giving away Wilson's aeronautical bent – its steel tube, aluminium and balsa wood construction was very much old-school, as were its non-adjustable wings.

Powered by a Chevrolet small block, the 1982 Aircraft Flyer Special – nicknamed the ‘Cropduster’ – was beset with handling difficulties from the off. It didn’t qualify and never raced again.

-

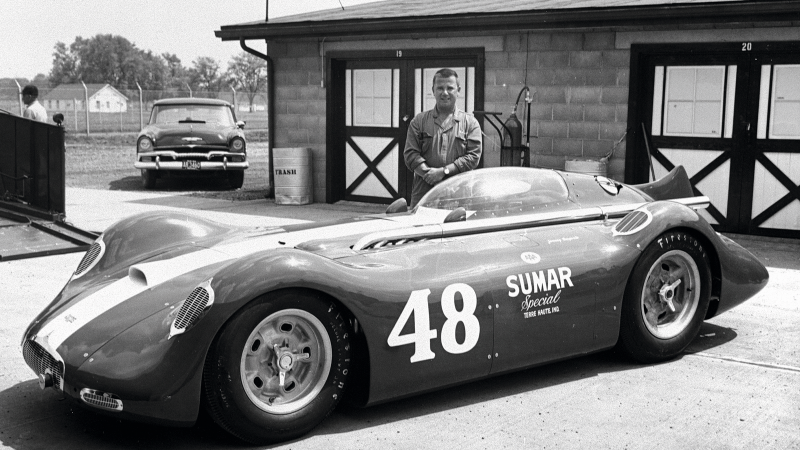

1. Sumar Streamliner

Based around a Kurtis-Kraft chassis and an Offenhauser engine, the idea behind the Sumar Streamliner was, as the name suggests, to be as aerodynamic as possible.

Good as that all-enclosed shell might have seemed, the oddball Indycar – which resembled a land-speed record machine more than an oval racer – was replete with problems from the off.

-

1. Sumar Streamliner (cont.)

Entered for the 1955 500, driver Jimmy Daywalt felt claustrophobic in the cockpit (which also hindered visibility), and wasn’t comfortable with the fact that he couldn’t see the front wheels.

The bodywork also defeated its own purpose by creating more drag, so it was removed during practice. In its ‘naked’ state, the car was quick enough to make the race at 139mph.

“That was the hardest drive I’ve ever had,” said Daywalt afterwards.