This 1938 D-series is a handsome Sedanca by HJ Mulliner, with a weatherproof sliding roof above the driving compartment.

It was sold new to a Mr Manuel Gomez Waddington, then residing at Claridge’s.

When war broke out he took it with him to America; it returned to Britain in the early ’50s, but went back in 1957 and had a series of owners in Connecticut, New York then Florida, where it acquired a white paintjob.

Current owner Chris Mott returned chassis 3DL32 to its factory maroon hue, and doubts the white leather is original.

Rear appointments are lavish yet tasteful, with picnic tables and companion sets, but no cocktail cabinet – the little central door gives access to the motor for the electric division, which turns the rear compartment into a cosy private office.

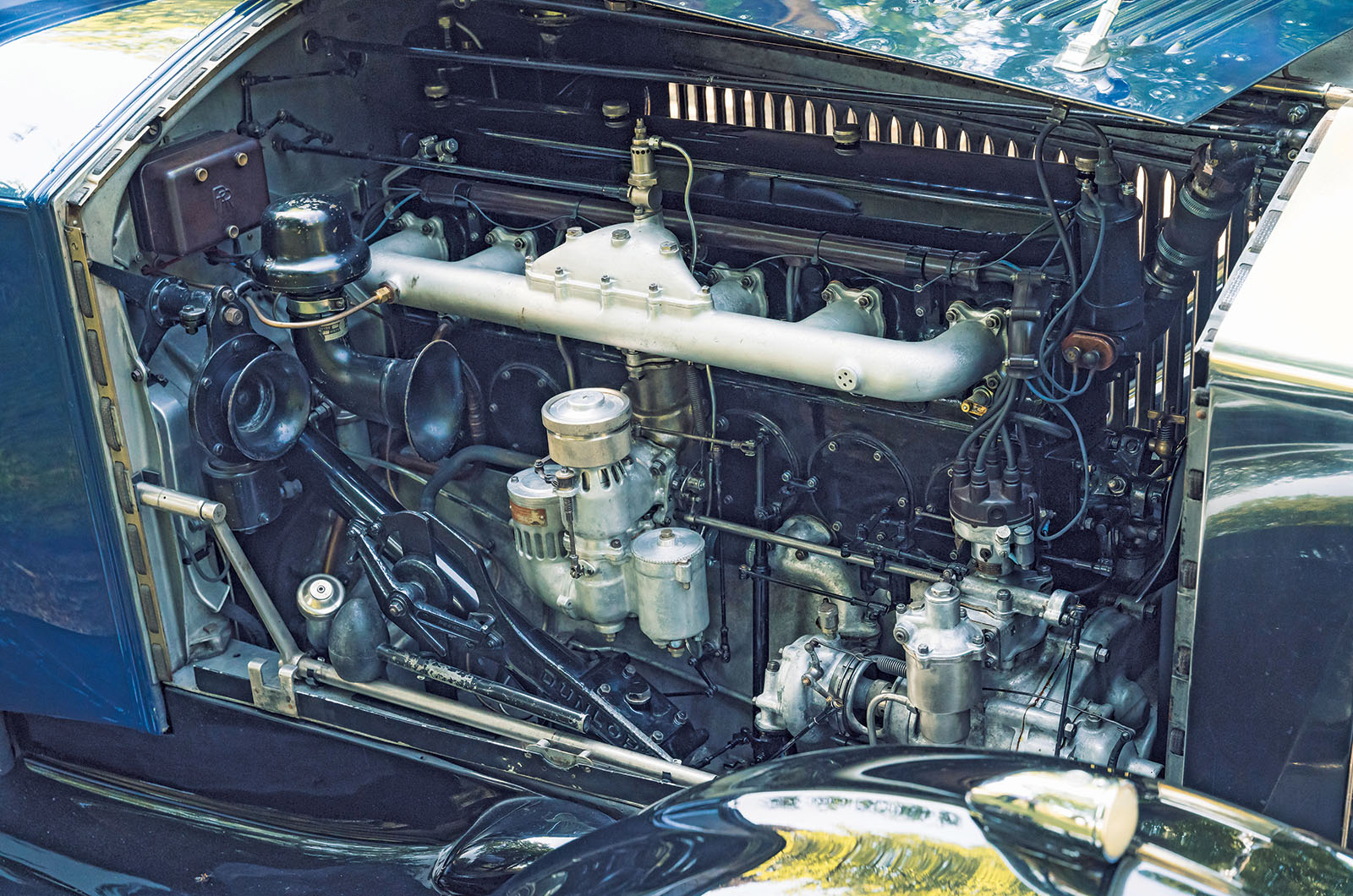

The Phantom III’s whispering V12 engine

Open the driver’s door and you notice the right-hand gearchange and, beside it, the dinky handbrake.

The driving position is ‘one size fits all’, with epic views over the massive, tapering bonnet.

Shuffling the huge wheel while manoeuvring gives you time to admire the Cuban mahogany fascia, with a 110mph speedometer flanked by smaller gauges, chromed knobs for interior lighting, plus a three-position switch for left/right fuel pumps, and even high and low horn settings.

Ticking over, the V12 could still be one of the quietest engines yet devised. With its independently timed banks of cylinders, lots of exhaust back pressure and a single downdraught carb, the focus was on silence and massive flexibility.

Using the gearbox is no chore, yet there is a fascination in slowing to 5mph in top then accelerating smoothly and seamlessly away.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom III’s elegant, tapering tail

There is no question of holding up modern traffic, although it tolerates rather than encourages fast cornering.

That said, the steering is silky, the brakes balanced, light and powerful, the ride soft but not soggy.

The Phantom III was, even to its disciples, a flawed masterpiece that set new standards of engineering excellence by taking an uncompromising approach.

Its detractors point to early reliability problems, demanding servicing requirements or bodies that were not always as elegant as those fitted to the Phantom IIs.

But perhaps its greatest crime was that, by sharing so little with the six-cylinder cars, the model denied its maker a profit.

If nothing else, it made the firm realise that concessions to commercial realities had to be made in subsequent, rationalised Phantoms.

Words: Martin Buckley

Rolls-Royce Phantom IV

Princess Margaret’s 1954 Rolls-Royce Phantom IV by HJ Mulliner sold for CHF2,255,000 with RM Sotheby’s in 2021 © RM Sotheby’s

Missing from our centenary line-up is the Rolls-Royce 1950-’56 Phantom IV.

Given that only 18 were built, strictly for royalty and heads of state, we can be forgiven for failing to capture one of the 16 survivors, none of which are in private hands in the UK.

These cars began the process of removing Daimler products from the frontline of British royal patronage, and were likely created as a result of direct overtures from the Duke of Edinburgh, who’d enjoyed an extended loan of the ‘Scalded Cat’ MkVI Bentley prototype.

The first Phantom IV was built for the late Queen Elizabeth when she was still a princess, in 1950.

Chassis 4AF2 was painted Valentine green and had all the latest interior refinements.

Just 18 Rolls-Royce Phantom IVs were built, and there are 16 survivors © RM Sotheby’s

Later, as Queen in 1954, Elizabeth took delivery of a Hooper-bodied landaulette, the first automatic Phantom IV.

Princess Margaret, the Duke of Gloucester and the Duchess of Kent also had them.

Despite the mystique surrounding these rare cars, the Phantom IV was so closely tied in, technically, with other Rolls/Bentley products that it wasn’t thought necessary to produce an official prototype – beyond the ‘Big Bertha’ straight-eight that was tested pre-WW2 as a replacement for the Phantom III.

The IV was based on a long-wheelbase Silver Wraith chassis, but with additional bracing, 10-bolt wheels, a 23-gallon fuel tank and a straight-eight engine mated to a manual ’box on all but the final five examples.

All were coachbuilt: nine by HJ Mulliner, seven by Hooper, and one each by Franay and Park Ward – the latter a works pick-up and test mule used for trying out the automatic transmission, among other things.

Queen Elizabeth II, Princess Margaret, the Duke of Gloucester and the Duchess of Kent were Rolls-Royce Phantom IV owners © RM Sotheby’s

General Franco had three armoured Phantom IVs by HJ Mulliner – two are still owned by the Spanish military – but the Hooper cars built for the Aga Khan and the heads of the Iraqi royal family are arguably the best proportioned.

The unhappy-looking Franay drophead made for Prince Talal Al Saud was the only car with non-British coachwork, and HJ Mulliner’s drophead (for the Shah of Persia) was the sole two-door.

The inlet-over-exhaust B80 was the largest in a range of four-, six- and eight-cylinder F-head engines developed for civilian and military use.

Suitably refined, it was believed to give c170bhp from 5.6 litres.

The troublesome Phantom III had cured Rolls-Royce of building in complexity just because it could, and the IV proved what could be achieved by applying the highest standards of engineering refinement to superficially ordinary solutions – if a straight-eight can ever be called ordinary.

Words: Martin Buckley

Rolls-Royce Phantom V

The Rolls-Royce Phantom V’s wheelbase is 21in longer than the Silver Cloud’s

Long-wheelbase versions of the six-cylinder Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith had served Crewe’s ‘mainstream’ limousine customers since the 1940s, but the introduction of the Silver Cloud II offered an opportunity to rationalise its chassis and drivetrain technology.

By going fully V8 across the range, Rolls-Royce designers could liberate some luggage space without affecting rear legroom or the balance of the lines.

Enter, in 1959, the new Rolls-Royce Phantom V. Under development since 1955, the V used a massive box-section chassis based on the Silver Cloud, but with an additional crossmember and tubular longitudinals accommodating an additional 21in of wheelbase.

Even with the shorter, lighter 6230cc V8 moved further forward, weight distribution was 47:53 front to rear and passengers in the back sat above the axle, enjoying effectively limitless legroom when the folding jump-seats were not in use.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom V’s sumptuous interior

There was no tie rod for the leaf-sprung (and lower-ratio) live rear axle, but otherwise the mechanical specification matched the Cloud, with two 1¾in SU HD6 carburettors, four-speed automatic transmission, power steering and Crewe’s famous, twin-leading-shoe drum brakes with mechanical friction servo.

Testing the near-£10k Park Ward limousine in 1963, The Motor noted that this vehicle for ‘topmost people’ was roughly the length of two Minis, cost twice as much as any other routinely listed production car and, at 2½ tons, had the performance of the average 1½-litre sports car.

Park Ward design number 980 morphed into HJ Mulliner, Park Ward design number 2003 in 1962, its quad-headlight styling brought into line with the Silver Cloud III and the lines modified above the waistline with a more razor-edged shape to the bootlid.

This VA (or ‘Phantom V½’) was mechanically as per the Cloud III, with 2in SUs, higher compression and improved power steering.

The Phantom V’s de rigueur cocktail cabinet

With HJ Mulliner, Park Ward amalgamated as part of Rolls-Royce, it fell to James Young to offer an independent alternative in the forms of its PV15 Limousine and PV22 Touring Limousine.

The Bromley coachbuilder also produced owner-driver versions, a handful of Sedanca de Villes and even a pair of two-doors.

This Midnight Blue PV22 was built for Lord Marks (of Marks & Spencer) and delivered in March 1964.

From the outside it remains, to my mind, the best-looking post-war limousine, of any make or model, with a hunched, almost sleek profile that provides a more private environment for the rear occupants.

The inviting rear bench is a piece of deeply bolstered fine furniture, trimmed in West of England cloth, with controls for the windows, radio and powered division in the armrests.

Rolls-Royce’s Phantom V shares its V8 with the Silver Cloud

The side-facing occasional seats emerge ingeniously out of the floor, and a cocktail cabinet is built into the division.

From behind the wheel, you soon forget the car’s length and the commanding driving position tends to quell any anxieties about the width.

The pre-engaged starter brings the V8 to life almost silently and the Phantom surges away on a silken ball of torque.

The gearchanges are there if you look for them, but it is a matter of instinct to flick manually between third and top for engine braking or accelerating out of corners.

The dashboard is much like a Cloud’s, with the classic ignition box, 110mph speedo and combination instrument centrally grouped.

The James Young-bodied Rolls-Royce Phantom V was styled by ex-Cunard man AF McNeil

The thin-rimmed, three-spoke wheel could be from a pre-war Phantom, rising at a shallow angle from between the floor-hinged pedals.

Like all the controls, the steering has a smooth action, so this giant car can be guided at a brisk trot with great sensitivity and satisfaction.

In all its forms the Phantom V maintained, perhaps even enhanced, the traditions and aims set out by its forebears.

Here was a refined means of high-speed transport, a business tool as much as a status symbol, that managed to be dignified without being pompous.

Words: Martin Buckley

Rolls-Royce Phantom VI

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VI can be hustled, despite its upright stance

Rolls-Royce had planned to make the 1968 Phantom VI a differently styled flagship, with more modern suspension.

In the end, however, it settled for an improved version of the HJ Mulliner, Park Ward seven-passenger limousine, incorporating updates that aligned it more closely with the Silver Shadow, but without adopting its high-pressure hydraulics.

Chief among these were a Shadow-type dash, separate front and rear air conditioning as standard, and the latest version of the 6230cc V8 with improved cylinder heads – which meant your mechanic could now change the spark plugs from under the bonnet, rather than from inside the wheelarches.

At first the only external telltale was the slightly shorter bonnet lids to incorporate a Silver Shadow-style air-conditioning intake on the scuttle; later came Corniche rear lights and front- rather than rear-hinged back doors to comply with EU safety regulations.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VI’s huge front bench

As before, the body was handbuilt on wooden bucks and wheeling machines from galvanised steel and aluminium, with parts of the structure in ash.

It was an unhurried process that took up to 20 months by the time the final cars were commissioned at the end of the ’80s.

Making each front wing took three weeks, there were seven separate panels in the massive roof and the electrical system incorporated three miles of wiring.

The rear suspension was still a live axle on leaf springs wrapped in grease-filled rubber gaiters, and giant crossply tyres were used until the end of production.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VI has seats for up to seven

Inflation, and the rising cost of man-hours in the strike-prone 1970s, drove the price up from £13,123 in 1968 (about the price of two Silver Shadows) to a spectacular £350,000 in 1988 – and that was just for the ‘basic’ model, before adding any extras such as silk curtains, twin telephones, a fridge or a television.

By then, annual production had dropped from 45 cars to fewer than a dozen examples, built alongside Corniches and Camargues at Hythe Road.

From 1973, HJ Mulliner, Park Ward was constructing the Phantom chassis in-house, although mechanicals still came from Crewe, upgraded in 1978 to the latest 6750cc V8 and three-speed GM400 gearbox.

The brakes were still massive drums, but now boosted by Silver Shadow powered hydraulics.

Rolls-Royce’s enduring V8 powered the Phantom VI

The Phantom VI never got disc brakes, and was the final Rolls-Royce to use carbs. It was also the last series-production car to be handbuilt on a separate chassis or feature a split, folding bonnet.

Finished in Velvet Green, this 1971 Phantom VI was ordered new by the chairman of Lloyds.

Most cars had leather in the front and West of England or twill cloth to the rear (a few even had Dralon-style Parkertex), but this one has pale-green Connolly hide throughout.

In the front you get a Shadow-style ‘Chippendale’ dashboard, complete with ‘Texas flap’ fresh-air intake and chromed eyeball vents.

The speedo goes up to 120mph but, still having the smaller engine, this particular car would presumably have similar straight-line performance to the Phantom V.

The softly sprung Phantom VI has plenty of roll

The 6230cc V8 comes with the old four-speed Hydramatic gearbox, sans torque converter, part-throttle kickdown or even a dedicated ‘Park’ position on the quadrant.

The Phantom VI is light and easy to drive. Acceleration is lively enough, and a sensitive pilot can drive around the slight abruptness of the gearchange by easing off in the right place.

You get a slightly better ride up front: at speed, rear passengers experience a boat-like wallow.

The view down the bonnet is magnificent, and a lack of adhesion on the leather seats is more of an inhibiting factor to swift cornering than tyre squeal or lurid roll angles.

Certainly, for the professional chauffeur there would have been worse days at the office (despite the limited seat adjustment on the working side of the glass division) than driving a Phantom VI for a living.

Words: Martin Buckley

Rolls-Royce Phantom V & VI oddballs

This Rolls-Royce Phantom V was built by Chapron of Paris on behalf of Hooper, which had only recently stopped trading © RM Sotheby’s

With the coachbuilding industry beginning to fracture by the late ’50s and early ’60s, special versions of the Phantom V were few and far between.

The Phantom V State Landaulettes were supposedly for royalty and heads of state only, but at least one was built for a private individual.

Chapron of Paris built two Osmond Rivers-designed limousines for American customers on behalf of Hooper, which had only recently stopped trading.

Three State Landaulettes were built by Park Ward, then a further two based on the ‘VA’ quad-headlamp Mulliner, Park Ward limousine before design number 2052 was introduced in October 1965, of which five were built ahead of the introduction of the Phantom VI.

Mulliner, Park Ward built five of these Rolls-Royce Phantom V State Landaulettes © RM Sotheby’s

Apart from the Canberra-style high-roof royal limousine, a certain number of State Landaulettes (fewer than 40), plus an armoured version of the MPW limousine, the only really ‘specialist’ Phantom VIs were by Pietro Frua.

The first was a vast, two-door drophead coupé commissioned by Swiss diplomat Simon van Kempen, who wanted a car to impress colleagues from rival embassies in Monte Carlo.

Rolls-Royce couldn’t supply anything outside its normal catalogue, but it would sell him a Phantom VI LHD chassis.

A £6265 rolling frame was delivered to Frua near Turin, in November 1971, via the Geneva agent.

This Phantom VI two-door drophead coupé was the work of Pietro Frua © Bonhams|Cars

The Italian stylist was commissioned to fashion a giant four-seater convertible on the same 12ft wheelbase, but Frua couldn’t speak English; with nobody at Crewe able to speak Italian, getting the right fittings was a long-winded affair.

Occasionally foreign parts, such as Mercedes-Benz door locks, were used to save time.

Frustrated by delays, the customer threatened to cancel his order, but must have been glad he didn’t when the car was finally delivered at the end of 1973, after making its debut at the Frankfurt show.

Highlights included dual heaters, storage bays under the centre-hinged bonnet for tools, and Fiat 130 Coupé headlamps.

This coachbuilt Rolls-Royce Phantom VI four-door took 20 years to complete © RM Sotheby’s

Powered by the familiar 6.3-litre V8, this two-door convertible – perhaps the biggest built in post-war times – was said to be surprisingly wieldy to drive, and van Kempen clocked up 300,000km in business and pleasure use.

Work on a less happy-looking four-door version, ordered by a British real-estate developer, began in 1973, but was still not complete four years later, by which time the customer had sold the project to an American collector.

It wasn’t finished until 1993, 10 years after Frua’s death.

Words: Martin Buckley

Rolls-Royce Phantom VII

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VII’s shape was all new, but it retained the traditional formality

‘Is the mighty Phantom a real Rolls-Royce?’ was the question Autocar posed when it tested the new Phantom VII in 2003.

Just four and a half years after BMW struck a deal with Rolls-Royce PLC (the Derby-based aero-engine maker) to acquire the Rolls-Royce automotive marque – and made another with Crewe’s new guardian, VW-Audi Group, to continue building the existing Silver Seraph at its plant until 2002 – a freshly reimagined Rolls-Royce Motor Cars had been installed in an all-new factory at Goodwood.

That it achieved all this, while simultaneously developing and launching a clean-sheet debut product, was remarkable.

But the Phantom VII needed to prove that Rolls-Royce’s new German custodian could produce more than just a rehashed, up-specced 7 Series.

Designed by Rolls’ Marek Djordjevic, the model quite rightly harked back to the 1956 Silver Cloud for its inspiration, rather than its more stately (and predominantly chauffeur-driven) Phantom VI predecessor.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VII’s huge, quad-cam V12

At just over 5.8m long, it retained traditional Phantom cues such as a long bonnet, wheelbase and rear overhang, as well as a downward-sloping boot, broad C-pillars and rear-hinged ‘suicide’ back doors (‘coach doors’ in Rolls-Royce parlance).

With a predicted 90% of owners expected to drive their cars themselves, the Phantom needed to handle and perform well, too.

Built around a rigid, light aluminium spaceframe, and riding on 22in rims (their ‘RR’-badged centres always upright), it employed double-wishbone suspension at the front and the 7 Series’ four-link system to the rear, with air springs.

The 760i’s quad-cam, direct-injection V12 was the natural choice of powertrain, the more so when its capacity was raised from 6 to 6.75 litres, matching that of the long-running L-series V8.

Rolls-Royce quoted (because it now had to) a maximum output of 453bhp at 5350rpm and an ample 531lb ft of torque at 3500rpm – sufficient to project this near-2.5-tonne behemoth from rest to 60mph in 5.7 secs, and on to a limited top speed of 149mph.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VII is a car for drivers, too

The interior was the work of designer Charles Coldham, successfully blending Rolls-Royce tradition into an unashamedly driver-friendly cabin.

The first owner of ‘our’ 2007 car (representative of the launch model, which wasn’t facelifted until 2009) was clearly not as extravagant when it came to options as many – so, alas, there’s no ‘Starlight’ headliner.

Enter the cabin through the vault-like door and you face a refreshingly simple but elegant dash, with just three dials before you for speed, fuel/coolant temperature and ‘Power Reserve’, the latter in effect replacing a conventional tachometer.

The slim, three-spoke steering wheel has the gear quadrant mounted above its electrically adjustable column.

Overall, you’d call the driving position imperious, putting you at a similar height to large SUVs.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom VII has a very capable chassis

To power up the V12, you slide the key into a slot in the dash and press the start button: it murmurs into life, but is barely audible.

Under way, the ZF ’box’s six ratios blur so effectively as you gather speed that acceleration is entirely linear and near-silent.

Only a modicum of wind and tyre noise intrudes – though both are well suppressed by double-glazed windows.

You’d never call the Phantom sporty, but it can be hustled with ease, rolling and pitching slightly (and appropriately), but retaining control of its huge body, even when driven in an unseemly manner.

The helm is nicely weighted, though largely mute, allowing you to drive at speed with commitment and accuracy.

The ride is superb: supple, beautifully damped and quiet, with only secondary surface imperfections upsetting the Phantom’s calm demeanour.

So, a real Rolls-Royce? As Autocar concluded back in the day: ‘Emphatically yes.’

Words: Simon Hucknall

Images: Max Edleston

Thanks to: Holdenby House; Tim Maltin and Chris Mott; Richard Biddulph at Vintage & Prestige for the New Phantom, V and VI; My Next Car for the Phantom VII

Factfiles

Rolls-Royce New Phantom

- Sold/no built 1925-’29 (1931 in USA)/3512

- Engine all-iron, ohv 7668cc straight-six

- Max power/torque not quoted

- Transmission three/four-speed manual, RWD

- Weight n/a

- 0-60mph n/a

- Top speed 90mph

- Mpg n/a

- Price new £1850 (chassis only)

- Price now £60-500,000*

Rolls-Royce Phantom II

- Sold/no built 1929-’35/1681

- Engine iron-block, alloy-head, ohv 7668cc ‘six’

- Max power/torque not quoted

- Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

- Weight n/a

- 0-60mph n/a

- Top speed 100mph

- Mpg n/a

- Price new £1850 (chassis only)

- Price now £60-500,000*

Rolls-Royce Phantom III

- Sold/number built 1935-’39/715

- Engine all-alloy, ohv 7338cc V12

- Max power/torque not quoted

- Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

- Weight 6100lb (2770kg)

- 0-60mph 16 secs

- Top speed 100mph

- Mpg 10

- Price new £1900 (chassis only)

- Price now £75-250,000*

Rolls-Royce Phantom V

- Sold/no built 1959-’68/196

- Engine all-alloy, ohv 6230cc V8

- Max power/torque not quoted

- Transmission four-speed automatic, RWD

- Weight 6000lb (2722kg)

- 0-60mph 13.8 secs

- Top speed 101mph

- Mpg 12.7

- Price new £9700

- Price now £50-250,000*

Rolls-Royce Phantom VI

- Sold/no built 1968-’90/365

- Engine all-alloy, ohv 6230/6750cc V8

- Max power/torque not quoted

- Transmission four-speed automatic, RWD

- Weight 6000lb (2722kg)

- 0-60mph 13.8 secs

- Top speed 101mph

- Mpg 12.7

- Price new £17,550

- Price now £50-175,000*

Rolls-Royce Phantom VII

- Sold/number built 2003-‘17/10,327

- Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 6749cc V12

- Max power 453bhp @ 5350rpm

- Max torque 531lb ft @ 3500rpm

- Transmission six-speed automatic, RWD

- Weight 5621lb (2550kg)

- 0-60mph 5.7 secs

- Top speed 149mph

- Mpg 18

- Price new £250,000

- Price now £40-130,000*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

We hope you enjoyed reading. Please click the ‘Follow’ button for more super stories from Classic & Sports Car.