The first post-WW2 motor race

The year 1948 was a significant one for British motoring and motorsport: on 18 September, racing was re-established with the inaugural fixture at Goodwood, and on 27 October the Earls Court Motor Show opened – both for the first time since hostilities had begun in September 1939.

Britain had excelled in – and arguably pioneered – circuit racing and motor shows prior to WW2, and seeing both returning was a welcome sign of normality in an economy ravaged by war and the austerity of rationing.

No surprise, then, that some 15,000 spectators headed to the Chichester track (created from the perimeter road at what was RAF Westhampnett) to see the flag drop at 2pm for the first post-war motor race.

Rumour has it…

The three-lap event, one of eight that day, was won by FC Pycroft in an unusual-looking Jaguar SS100, seeing off a small field of Healeys and an HRG from the back of the grid.

Just over a month later, the Jaguar SS100’s replacement, the XK120, blew the lights out at Earls Court when it made its spectacular debut.

Jaguar aficionados have long surmised that there may be a link between the two events…

Motorsport influence

That’s certainly the case in the view of Paul de Ferranti Craddock Pycroft himself: in 1984, right here in Classic & Sports Car, he contested marque historian Paul Skilleter’s assertion that Jaguar boss William Lyons had not copied his design for the XK120, after Pycroft demonstrated his unique, aerodynamically bodied SS to the works in 1947.

At face value Pycroft’s claim was not outlandish, given the cars’ similarities, but historians contend that the XK’s final lines owe more to the influence of the BMW 328 that featured on the 1940 Mille Miglia.

Also that its shape had been defined by a factory prototype, for which photographic evidence exists, as much as a year before Pycroft’s trip to Foleshill.

Star car

Whatever the link, his special-bodied SS100 made an impression on anyone who saw it.

And plenty did when it took the chequer in that inaugural race, with Motor Sport fronting its report with a photograph of the car in the lead.

But 35-year-old Paul Pycroft was no stranger to success, having campaigned his 2½-litre SS100 from the get-go after taking delivery in November 1936.

The start of the story

Chassis 18045 was delivered through Henlys of Piccadilly with a Riley Imp taken in part exchange.

Pycroft recalled the Riley in a letter to fellow SS100 owner Michael Shelley nearly five decades later, declaring it: ‘Just a pretty face and not much else.’

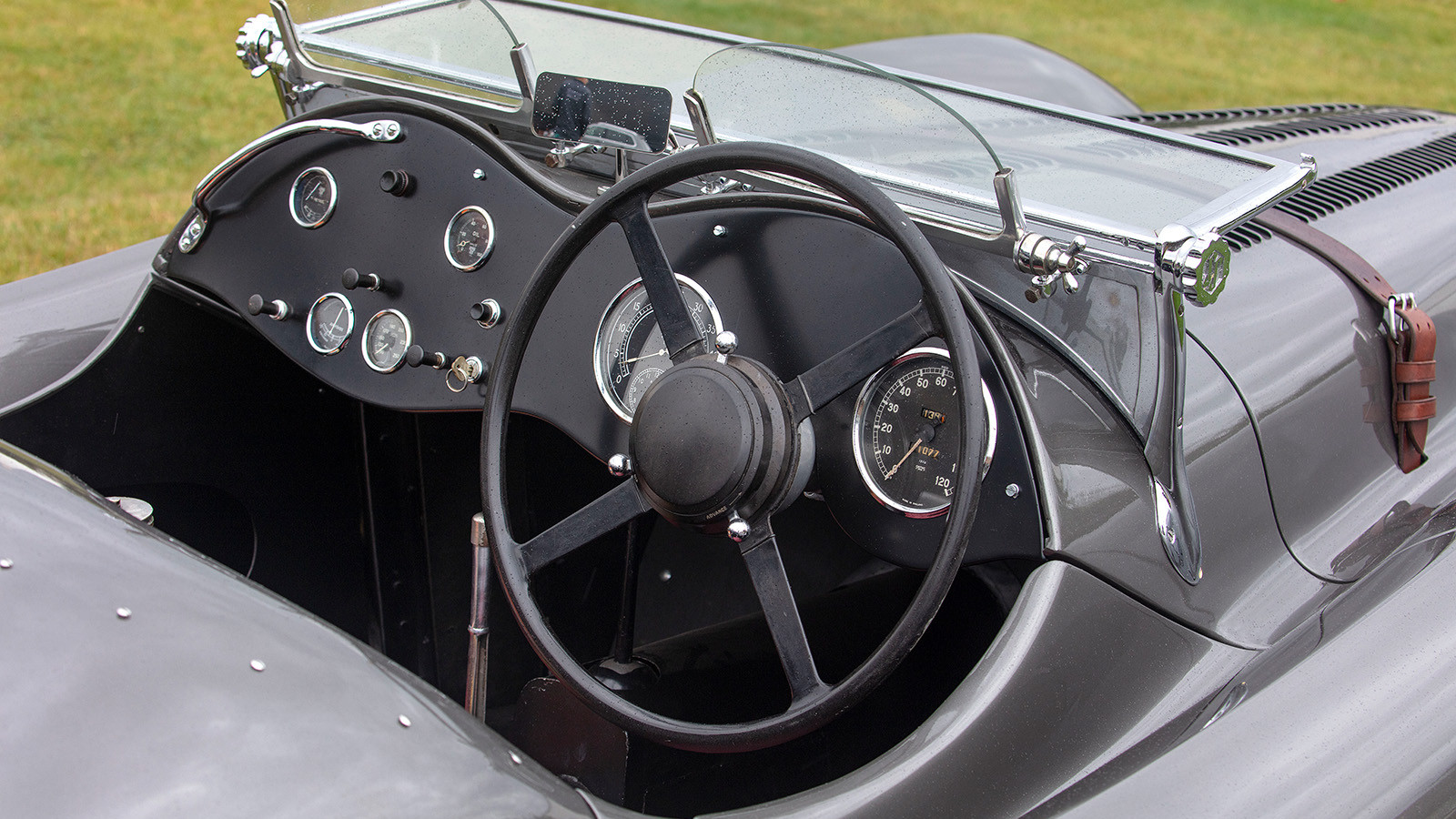

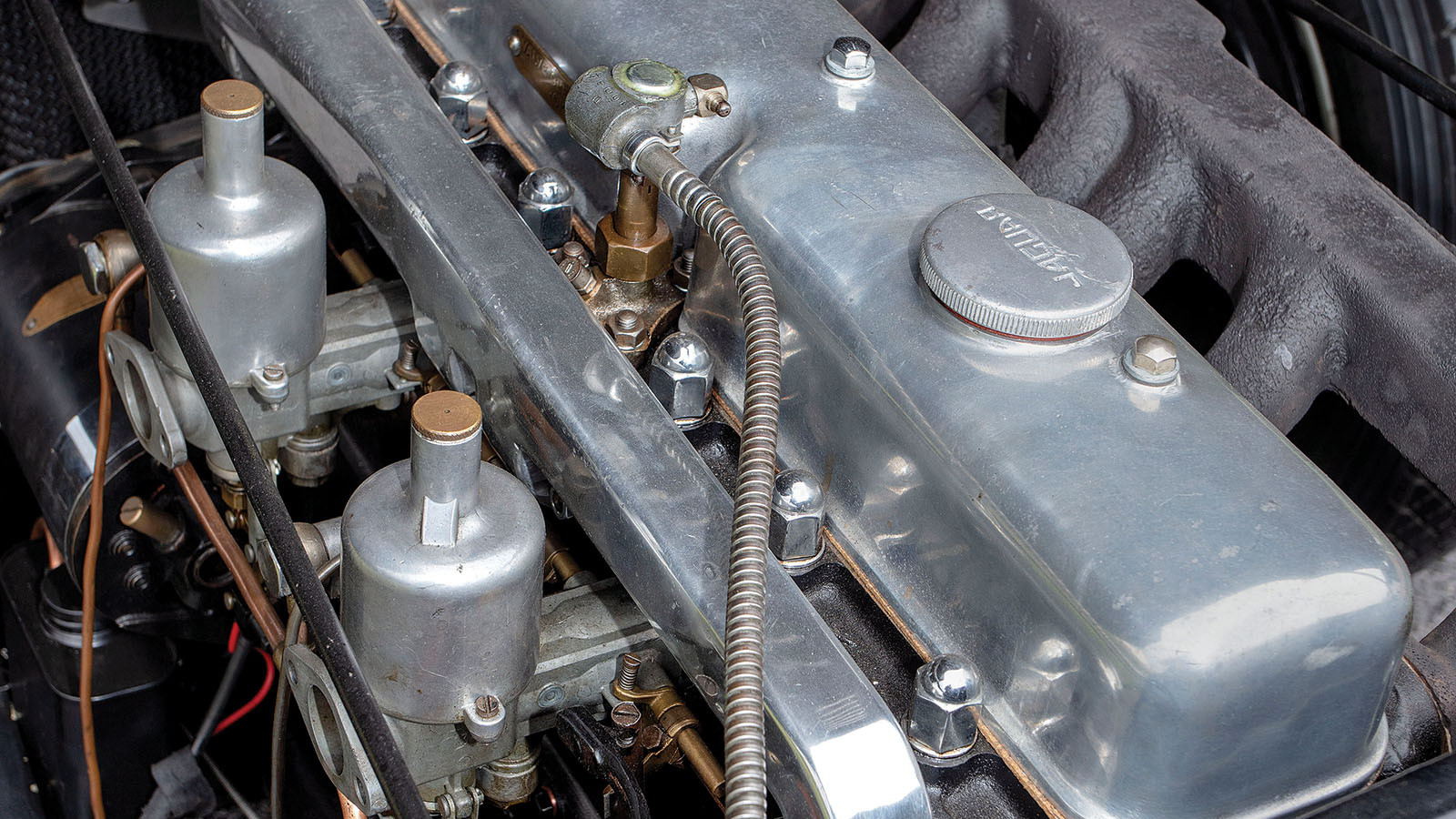

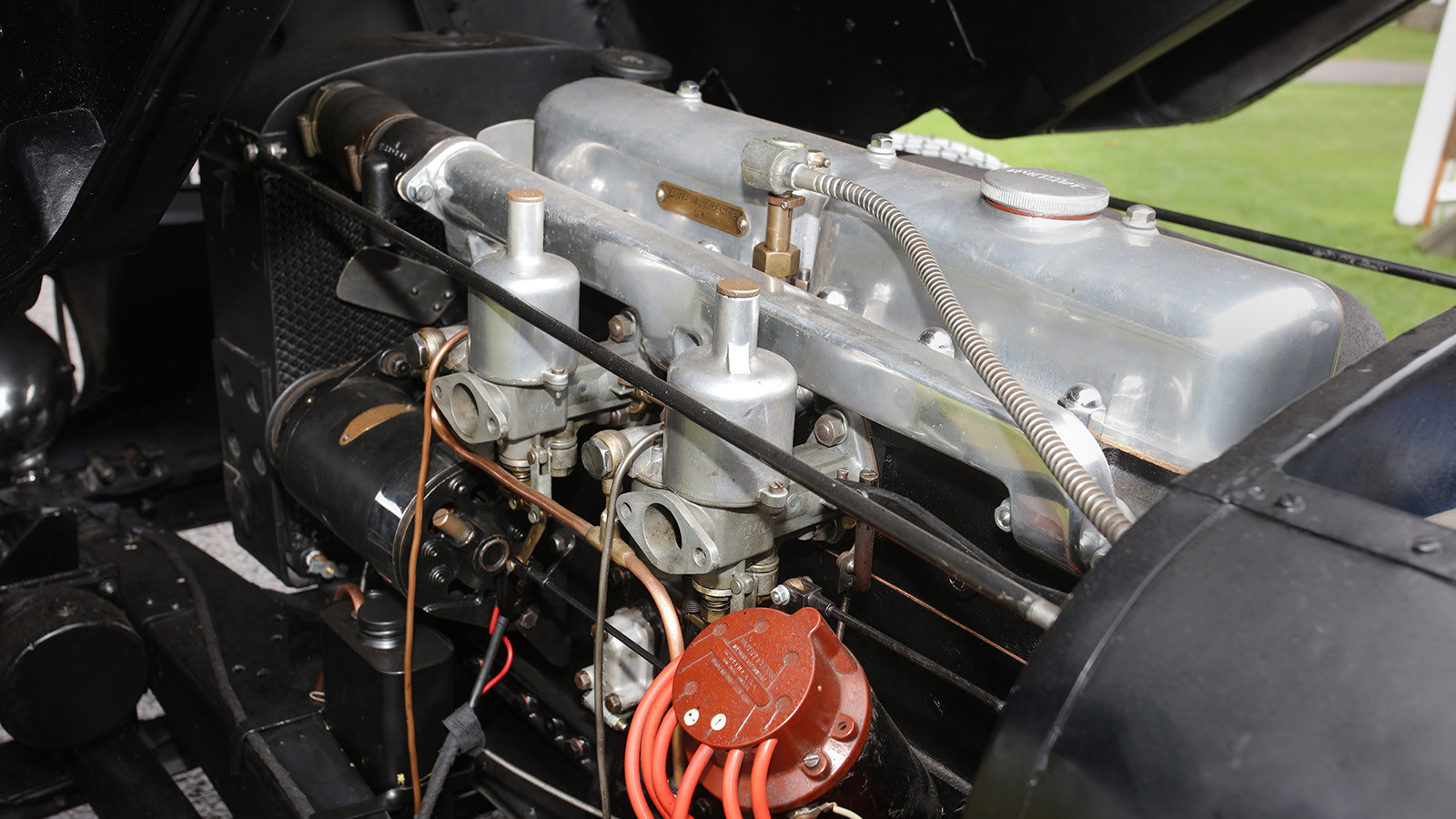

The correspondence with Shelley provides insight into Pycroft’s SS100, such as it being specified with a Scintilla Vertex magneto – ‘I did not trust sparks by Lucas in those days’ – and an adapter to take twin spares ahead of an imminent move to Switzerland.

Back to the works

Pycroft started campaigning the SS100 in local events, taking third in the 1937 Swiss hillclimb championship despite missing the first and last rounds.

A year later he returned to the factory for a ‘works overhaul’, only for the SS100 to snap a conrod while on test.

Jaguar replaced the engine for free, but Pycroft had to pay £5 for a new gearbox.

He later had to wire the factory for further transmission parts after the SS100 got stuck in top on a trip to Lake Constance.

A new look

He wrote: ‘I drove home over several mountain ranges and through a very dramatic storm, a distance of 200 miles in top gear. Quite a car!’

Soon after that, Pycroft modified his car’s bodywork in a bid to gain a competitive edge: ‘I found a very efficient body shop who, to my design, cut out the running boards and made a valance to the front wings and filled in the rear ones.’

He then entered the Paris-Nice rally: ‘Enormous fun, but unsuccessful due to my lack of experience in this type of event.’

Friendly rivalry

Better luck followed in a hillclimb event at La Turbie, where he beat Tommy Wisdom in a works SS100.

A year later he repeated the feat, by which time Wisdom had been upgraded to the ex-Charles Follett Lightweight Railton.

‘This was not considered funny,’ was Pycroft’s delighted comment to Shelley.

In April 1939 he again trounced Wisdom when he finished eighth in the Paris-Nice rally, but months later war broke out and the SS100 was laid up.

Post-war makeover

When peace returned, Pycroft set about updating the styling of his by then 10-year-old Jaguar.

‘I found a brilliant panel-beater and started construction of the way I felt a two-seater should look,’ he wrote.

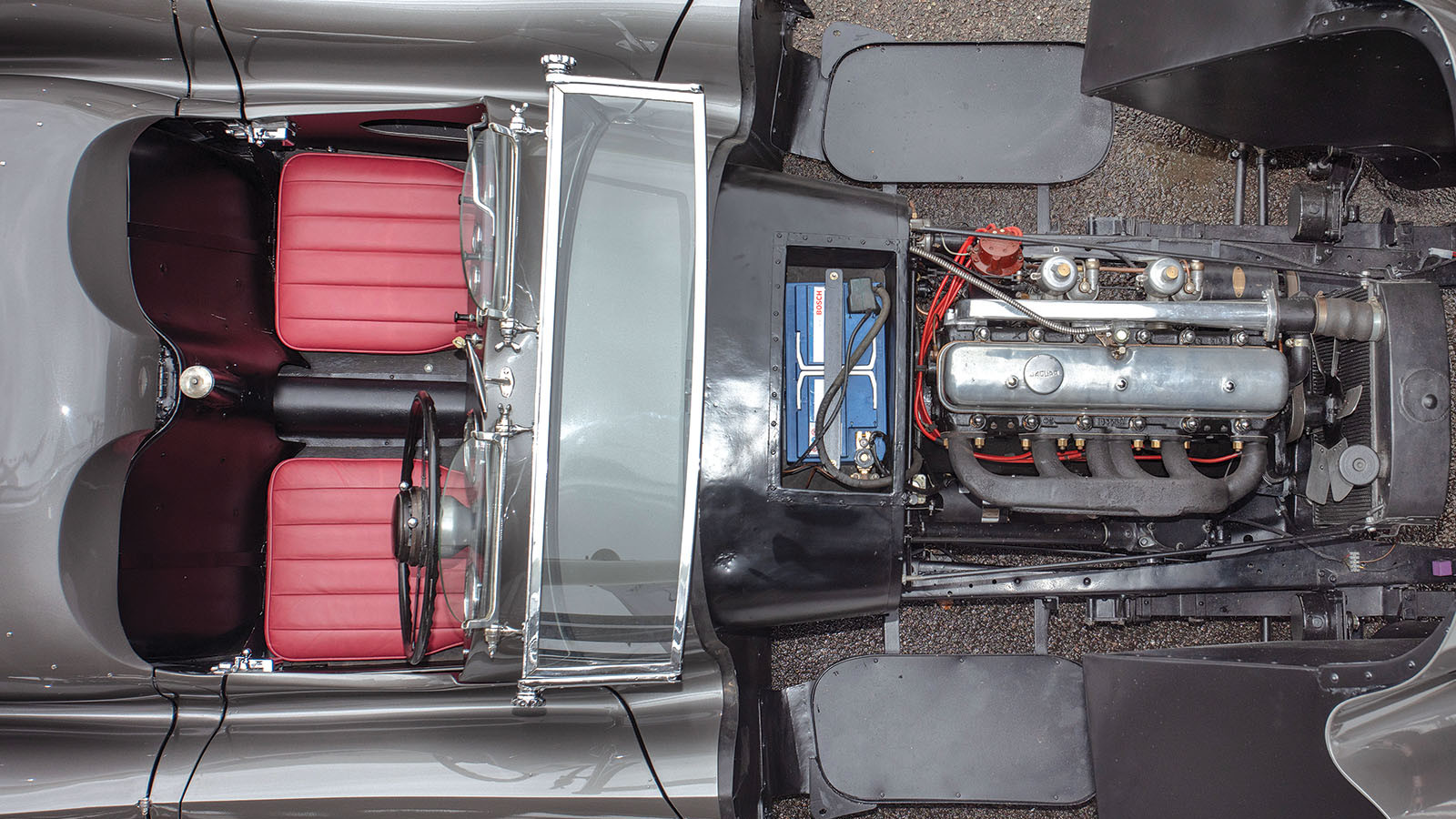

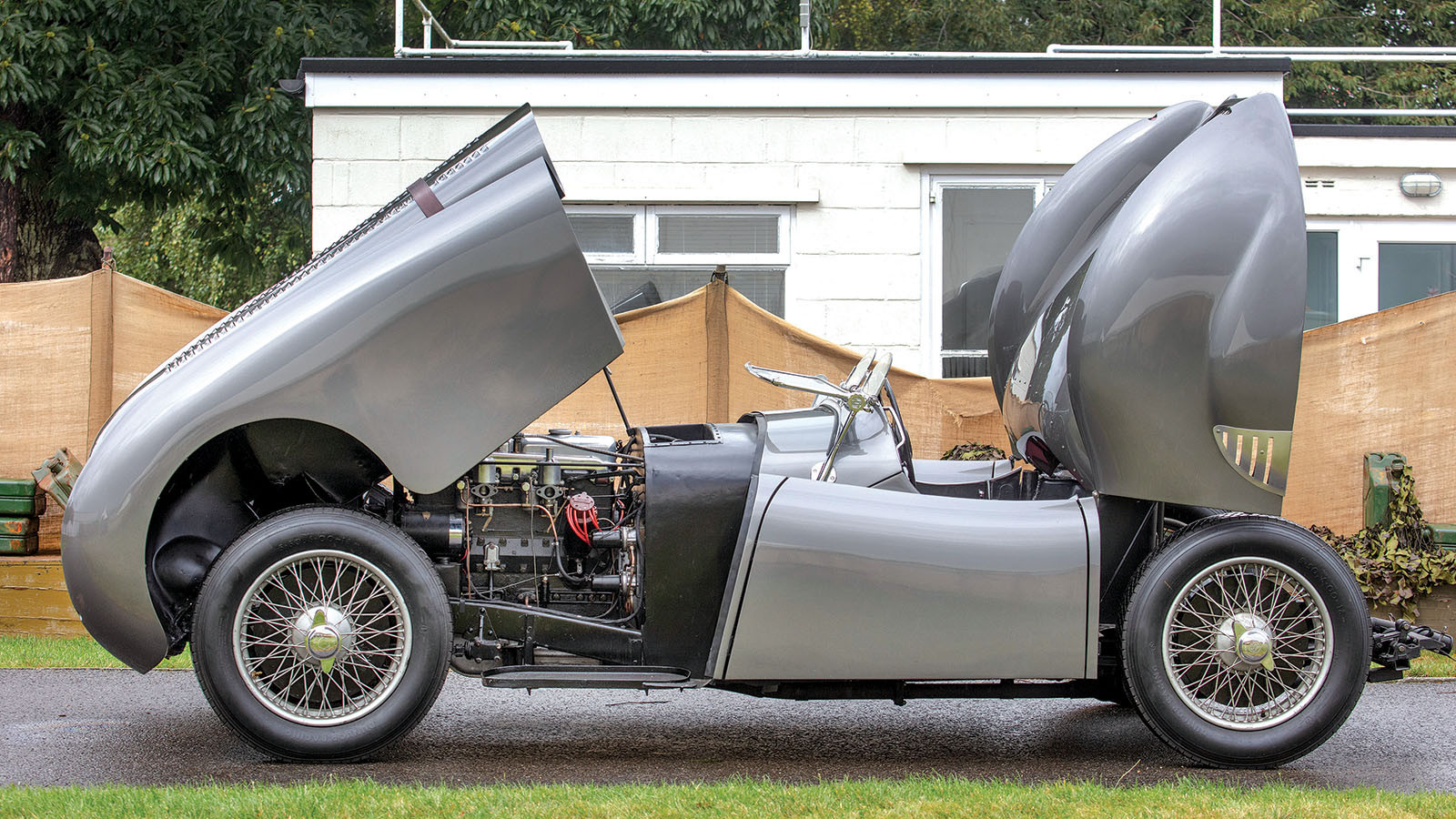

It centred around a double pontoon shape with the front and rear wings as one-piece units that hinged open, which Pycroft felt made the car a leader in terms of design.

Let’s be practical

It’s clear from his letters that Pycroft’s efforts were quite considered: ‘An outrigged pannier was bolted to each side of the chassis ahead of the central bulkhead and on to which baggage could be placed and sealed in the normally wasted space within the front wings.’

Pycroft also adjusted the centre of gravity by relocating the fuel tank – boosted from 14 to 21 gallons to give a range of nearly 500 miles – to behind the rear seats.

The rebody kicked off in June 1946, just over a year before the trip to Jaguar to show it off.

Winning ways

A month later, in August 1947, he campaigned it with success in The Ulster Trophy Race, then took part in the Brighton Speed Trials in September, clocking a fastest speed of 62.48mph.

The Motor opted to run a full page in its 12 November issue showing a three-dimensional technical drawing of the car with its one-piece front and rear shrouds open.

Some 10 months later, Pycroft’s creation was on the grid for race one at Goodwood: a three-lapper for ‘Non-supercharged Closed Sports Cars up to 3,000cc’.

From the back

Pycroft’s creativity had extended to a two-piece hardtop, making the car eligible for the class. But he drew the short straw in the grid ballot and lined up at the back.

Pycroft soon took the lead and never lost it. His fastest lap was 2 mins 6.6 secs, and he passed the chequered flag at a 66.42mph average – with one hand holding the roof down.

The meeting also featured a new kid on the block: first in race five was 18-year-old S Moss, making his debut at the wheel of a Cooper.

A hard goodbye

But the day’s main grid was the five-lap Goodwood Trophy, featuring a clutch of Maseratis and ERAs, and the likes of Roy Salvadori, Duncan Hamilton and Reg Parnell, the latter taking the victory with an average speed of 80.56mph.

British circuit racing was back with a bang.

In 1949, Pycroft returned to the Continent to compete in the Stella Alpina in Trento, Italy.

But he soon moved on to other racing interests and in 1951 sold the car to Performance Cars Ltd on London’s Great West Road, to fund the purchase of an Emeryson Formula Three racer.

Seller’s remorse

He went on to regret the decision, describing the Emeryson as: ‘Interesting, but a disaster.’

The Pycroft Jaguar was later in the custody of Kenneth Warner, (brother of Graham, of dealer The Chequered Flag), and it had two further owners before coming up for sale with Coronation Cars in September 1967.

The advert was seen by current keeper Alexander van der Lof’s late father, Dries, in The Netherlands.

A safe pair of hands

Dries was the country’s first Formula One racer – he competed in the 1952 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort – and later founded the Dutch Historic Automobile Racing Club.

He was also a former SS100 owner and looking for another, and he made a successful offer of £180.

Van der Lof Snr was no stranger to coachbuilt cars. “In 1952 he put an aerodynamic body on an MG TD chassis, with help from his father’s company,” says Alexander.

“He learned a lot and had the technical knowledge to repair and build cars.”

Who built it?

“My father passed away in 1990, and by then the body was outside,” adds Alexander.

“I believe he was very close to getting rid of the shell – we also had an old Ferrari 330GT body and threw that away. In those days it was worth nothing and we needed the space!”

A question mark remains over who built the Jaguar’s unique coachwork.

Post-war there was a shortage of materials, but, thanks to aircraft construction during WW2, no shortage of skills.

The Jaguar’s maker

Pycroft never mentioned who he chose, but coachbuilding historians have long pointed to Lionel Rawson of the Slough-based firm John Colinsons.

Rawson was an ex-aviation man and by all accounts a pioneer in the UK of the all-metal body, eschewing traditional timber-framing.

The firm was in business for around a decade from 1947 and bodied a few Jowett Jupiters and several Healeys.

Back to life

“I always thought it was a rather unique design and had the intention of rebuilding it on a donor chassis,” says Alexander.

“Then 15 years ago I discovered the story of the Pycroft Jaguar and its win in the first race at Goodwood.

“I decided that the only option was to put the body back on to the original chassis.”

In 2017, Alexander engaged Alwin Hietbrink of Dutch firm Hietbrink Coachbuilding to bring the Pycroft Jaguar’s remains back to life.

Skilled work

“He builds replica bodies, but he has also restored some extraordinary Ferraris and is skilled in retaining originality,” says Alexander.

The goal was to keep as much original metal as possible.

“There was some corrosion on the edges and he had to weld in new pieces, which was difficult with such old aluminium,” recalls Alexander.

“We found small differences on each side. It looks as if one coachbuilder was working on the left and another on the right.”

Goodwood return

The strip-down revealed the car’s authentic metallic hue, allowing the colour to be matched – with a section of the original finish under the one-piece bonnet maintained for posterity.

The restoration swiftly gathered pace after Goodwood announced that the 2023 Revival would mark the 75th anniversary of the circuit’s opening.

“It was important to have the Jaguar there,” says Alexander, who drove the SS100 for the first time only the weekend before the Revival, where founder Lord March was at the wheel to open the circuit each morning.

First-hand experience

Returning to Goodwood today gives a chance to experience how Pycroft must have felt all those years ago.

With the high, narrow scuttle (retained from the original body), the Pycroft still feels like an authentic SS100.

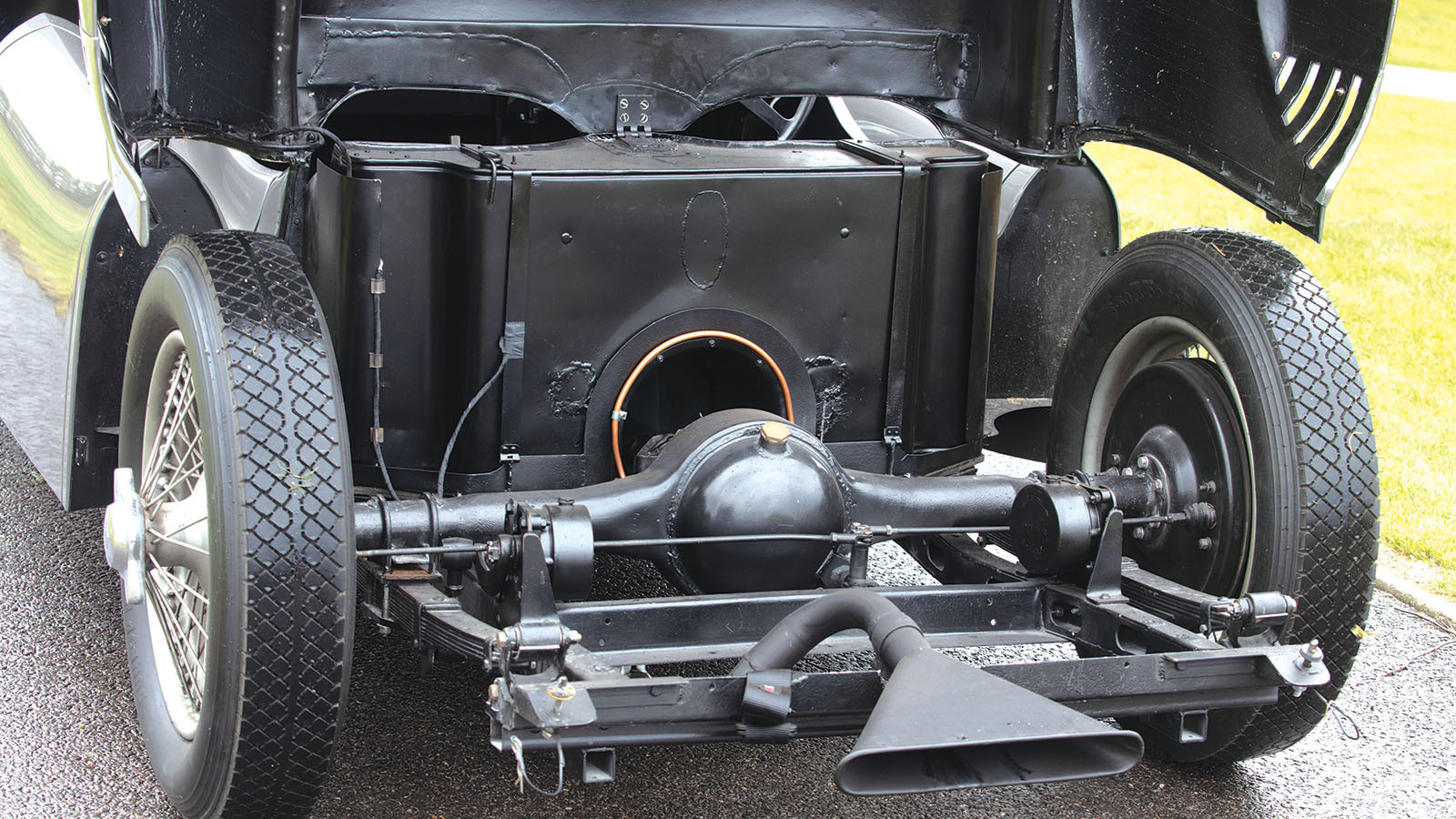

It’s the same with the controls: the tight gearchange and wooden feel to the rod-operated Girling drum brakes lend a distinctly pre-war sensation, at odds with the aerodynamic post-war styling.

As speeds build it feels more planted, with none of the typical SS100 front-end lightness.

More punch

The aero changes improve performance, too, despite the body’s extra 110lb/50kg or so.

‘In spite of the weight increase over the standard SS100, 0-60mph acceleration improved by 10%,’ wrote Pycroft. ‘Frank Costin could tell you why!’

Tweaks to the straight-six motor also help. “The engine had been assembled with a tuned and flowed head,” says Alexander, “plus high-compression pistons and aluminium conrods.”

The wide side pontoons and repositioned fuel tank to allow for the elegant tail mean the cockpit is cramped.

Bit of a squeeze

Alexander has omitted the seatbacks to boost space, leaving only the short squabs to temper the hard ride.

While the leather is period-correct, the interior had a more outlandish finish in Pycroft’s time.

‘The seats were covered in leopardskin,’ he wrote, ‘made by my mother from skins I found in the Caledonian Market in London… Youth could be permitted some vulgarity in those days.’

Career highlights

It’s a reminder that Pycroft was only 23 when he ordered the SS100, which was just one of many chapters in his motorsport career.

He was a regular at hillclimbs in the 1950s, campaigned an E-type on the Continent in the ’60s and raced a BRM P126 to third in the 1970 RAC Sprint Championship.

He also competed in a three-hour race at Le Mans in the works Costin Amigo, which he had helped finance.

Pycroft continued to defend his claim over the origins of the styling for Jaguar’s post-war sports icon.

Home is where the heart is

Writing from his home on Anglesey in May 1992 (eight years before his death, aged 86), he said: ‘I always maintained that Jaguar stole my body design for the original XK120.’

Whatever the truth may be, Pycroft’s striking efforts to rebody the SS100 – along with his skills behind the wheel that famous day in 1948 – have created a special place for this car in the history of both the marque and the circuit.

“There might be other races where the Jaguar would be a good fit,” smiles Alexander, “but I believe it belongs to Goodwood.”

Thanks to: Goodwood; Paul Skilleter; Terry McGrath motoring archives

We hope you enjoyed this gallery. Please click the ‘Follow’ button above for more super stories from Classic & Sports Car.