The soft-top Mantula Spyder was launched in 1985, and the convertible soon became a popular concept for Marcos; most models from then on came in Spyder rather than coupé form.

The Mantula was superceded in 1992 by the factory-built Mantara, while the Mantula had also been available in kit form.

A couple of hundred were produced, including all the kits, but it is believed that not all of those have been built.

Despite being born in 1991, this Mantula’s accessories – that colour-co-ordinated spoiler and those alloys – feel as if they belong to the previous decade.

The low driving position in the Marcos Mantula offers legroom but not comfort

The driving position is so reclined that it engenders a degree of awkwardness, akin to stumbling into somewhere decadent and leathery run by Cynthia Payne.

Although there is plenty of length in the footwell, thanks to an electrically adjustable pedalbox, the cabin and the footwell are both narrow and there is no space reserved for your left hoof.

The (rather optimistic) 200mph speedometer and the 6000rpm rev counter – with 5500rpm redline – are both obscured by the dashboard’s top rail and the steering column.

The ride is firm, the steering a crafted blend of ease and beefy feel.

The Marcos beats the TVR for feel

The front-end responses, just like the helm, come as a genuine surprise.

The Mantula’s body control is strict and, although that firmness means it does a sideways shuffle through undulations, discretion advises against goading the rear into showing off.

The gearbox is everything you could hope for: the chunky gearknob fills your palm as the lever is pumped through the well-spaced ratios, and the change is short, sharp and wonderfully weighted.

The offbeat exhaust note is positively scrumptious – it’s smooth and burbly, backed up with a slight gear whine.

How to pick between Morgan Plus 8, MGB GT V8, Triumph TR8, TVR 350i and Marcos Mantula?

The Mantula really does feel impressively at home on the track and, measured purely by dynamic ability, the Marcos takes the win from the TVR.

Its shortfall in factory-claimed power output – 173bhp at 4550rpm versus the 350i’s 197bhp at 5280rpm – is compensated for by the Marcos’ lower weight (1962lb versus 2564lb), which results in a quicker time to 60mph.

Stylistically the Mantula is a bit hit and miss, but come to terms with its oddball essence and driving one is a petrol-powered tonic.

After the fifth of five, the time has come to make a decision.

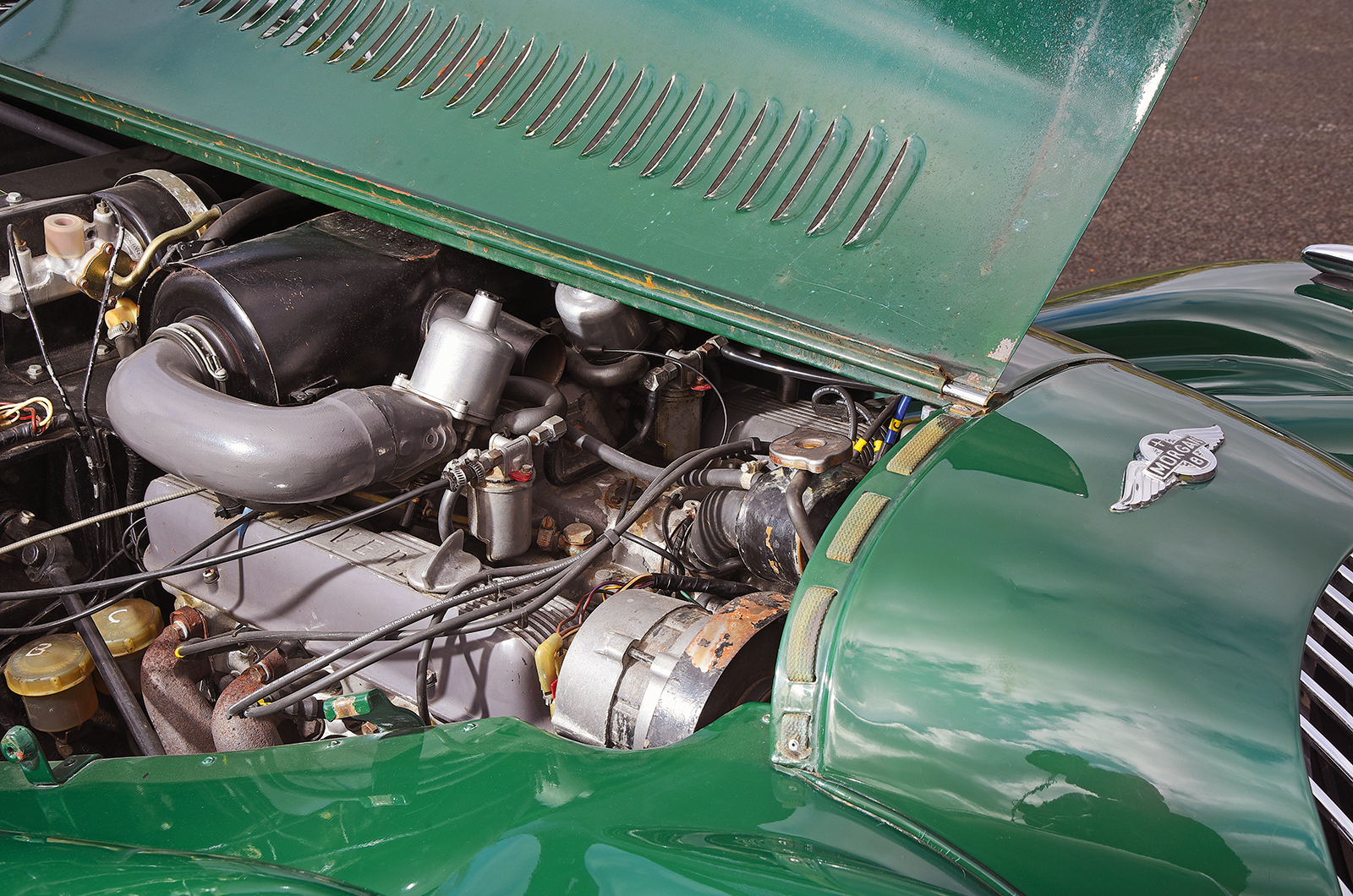

If your heart is truly set on a Morgan, it’s the only car that will scratch that itch

On public roads the Morgan depends rather too much upon the pliability of its occupants’ spinal columns – but if you want a Morgan, then only a Morgan will do.

In respect of the duelling Leyland GTs, it is easy to be too harsh on the TR8 because it is a US model, which was really intended to lope along miles of shimmering two-lane blacktop with the wind in your perm.

If the suspension spec – particularly the spring rates and dampers – were more to UK tastes, then most of its criticisms would be addressed.

The MG wins the battle of the Leyland GTs

But here and now, I’d have to opt for the MG.

To paraphrase its owner: the GT V8 doesn’t do any one thing brilliantly, but it does everything well.

Comfortable yet compact, attractive yet practical, with build quality that persistently was at the top of BL’s internal league tables, and all with a dusting of MG charisma.

Why on Earth wouldn’t you?

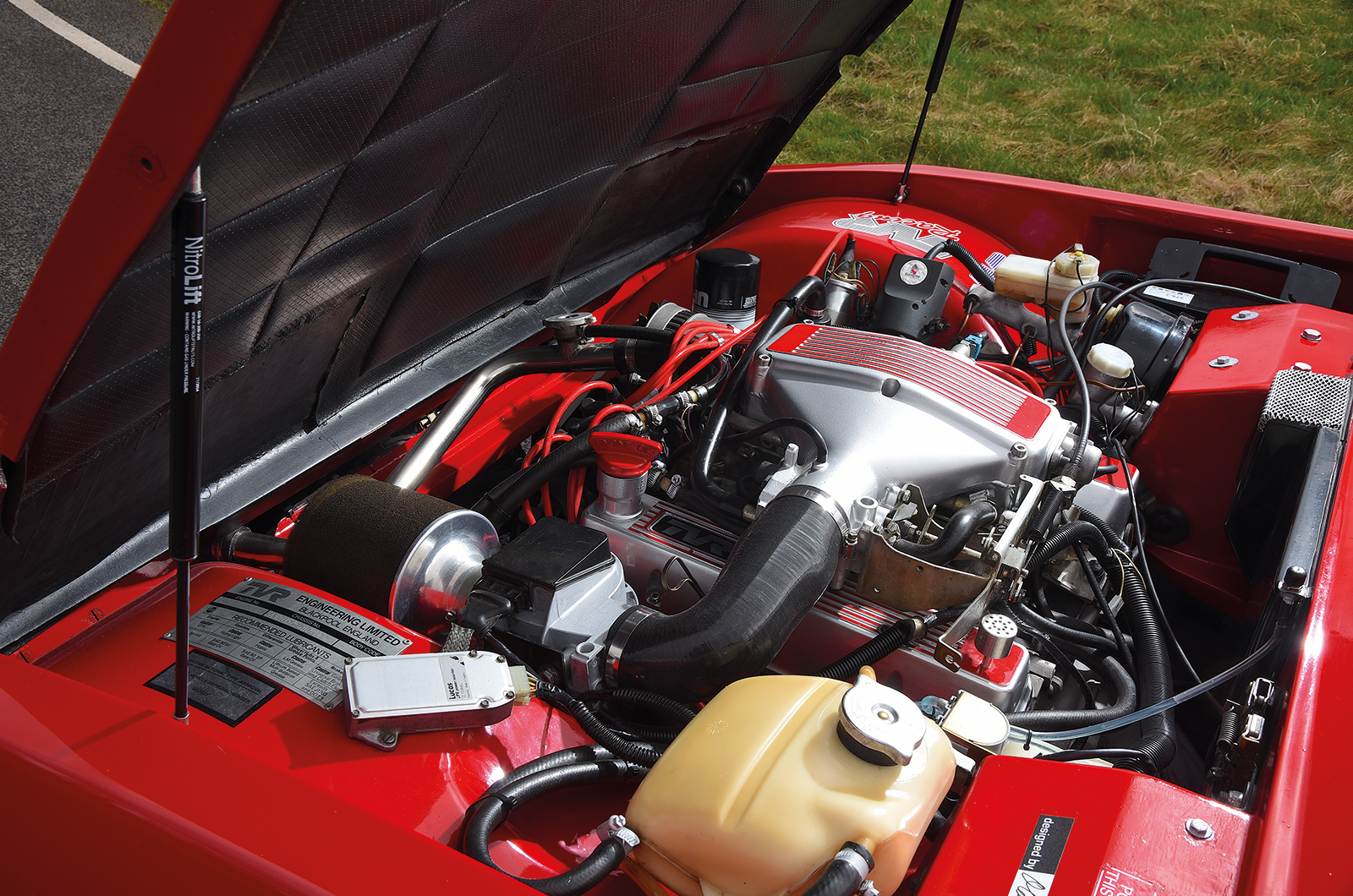

The TVR triumphs over the Marcos, too

As for which plastic is more fantastic, unless (unlike me) you can comfortably fit into the Mantula, then it has to be the TVR.

The 350i has re-ignited a longstanding Blackpool itch.

Dynamically it is on the sports-car money and its driver can merrily howl through big mileages without a fear for their comfort.

Images: Will Williams/John Bradshaw

Thanks to Keith Belcher; Christopher Kenneth Smith; Steve Morgan; Neal Callaghan; Richard Thorne Classic Cars; TVR Car Club; MG Car Club; TR Register; Morgan Sports Car Club; Club Marcos International

This was originally in our June 2019 magazine; all information was correct at the date of original publication

READ MORE

The best MG that might have been?

Brave new world: TVR Cerbera vs Lotus Esprit

Don’t buy that, buy this: Jaguar E-type vs Marcos 3-Litre

Simon Charlesworth

Simon Charlesworth is a contributor to Classic & Sports Car