Remembering some of the racers that fought, as Goodwood marks 75 years since the D-Day landings

Sydney Charles Houghton Davis was 52 in 1939. No age to pick a fight. Yet for ‘Sammy’, and for so many others, ‘The obvious thing was to get into this war one way or another and help with all one’s power whatever might result.’ So he wrote in A Racing Motorist.

This was a man of skills aplenty. A veteran of WW1, he demobbed into journalism as sports editor of The Autocar. And sporting he was, runner-up at Le Mans in 1925 in a Sunbeam and winner as a Bentley Boy in 1927, having crashed from third in ’26. The prototype Paul Frère.

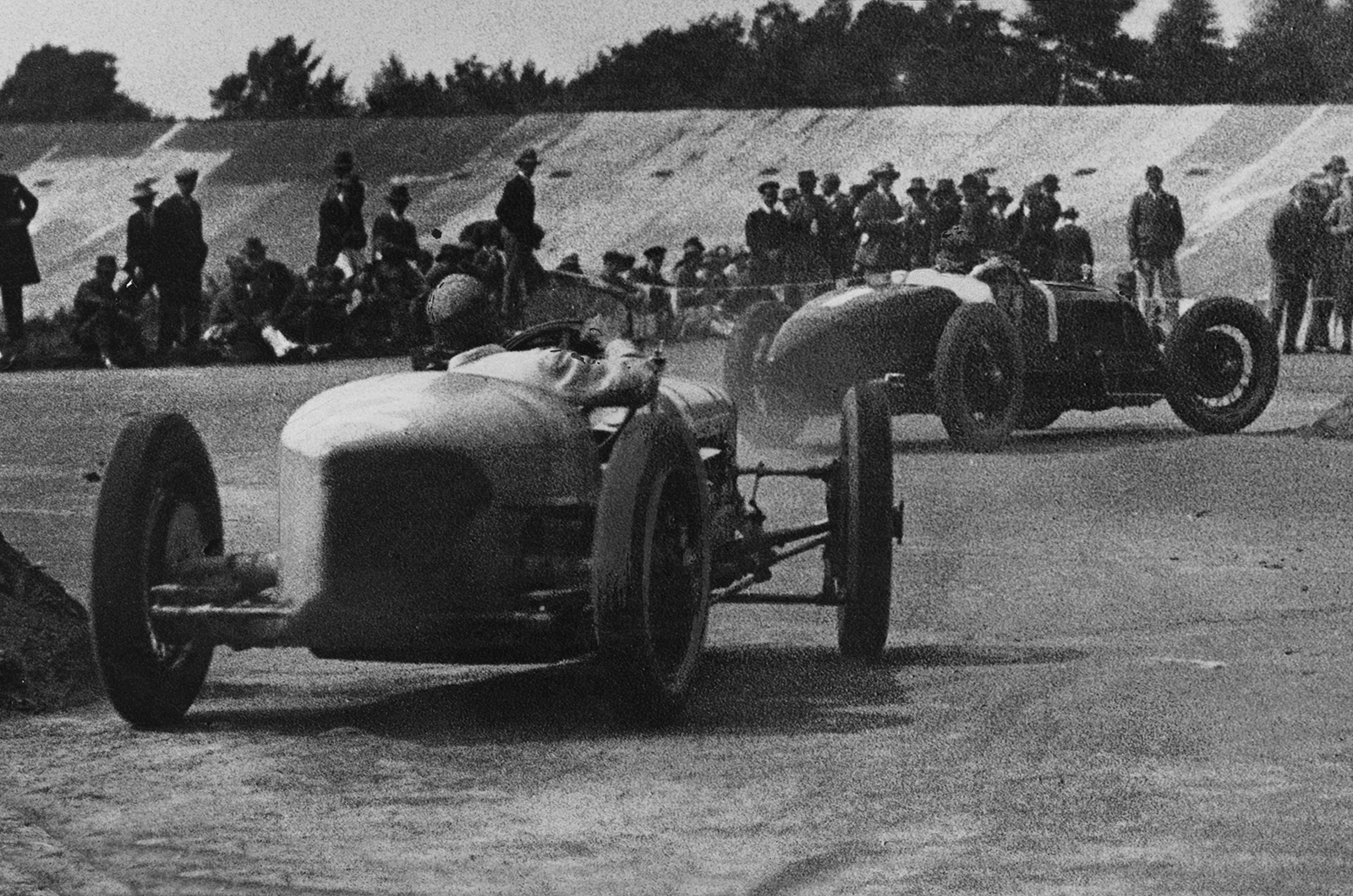

His racing talents weren’t reserved for La Sarthe, though, regularly featuring at the front at Britain’s former military base Brooklands – itself soon to re-enter the theatre of war.

He would have joined an anti-tank battery until some ‘bussybody [sic] became inquisitive about my genuine age’.

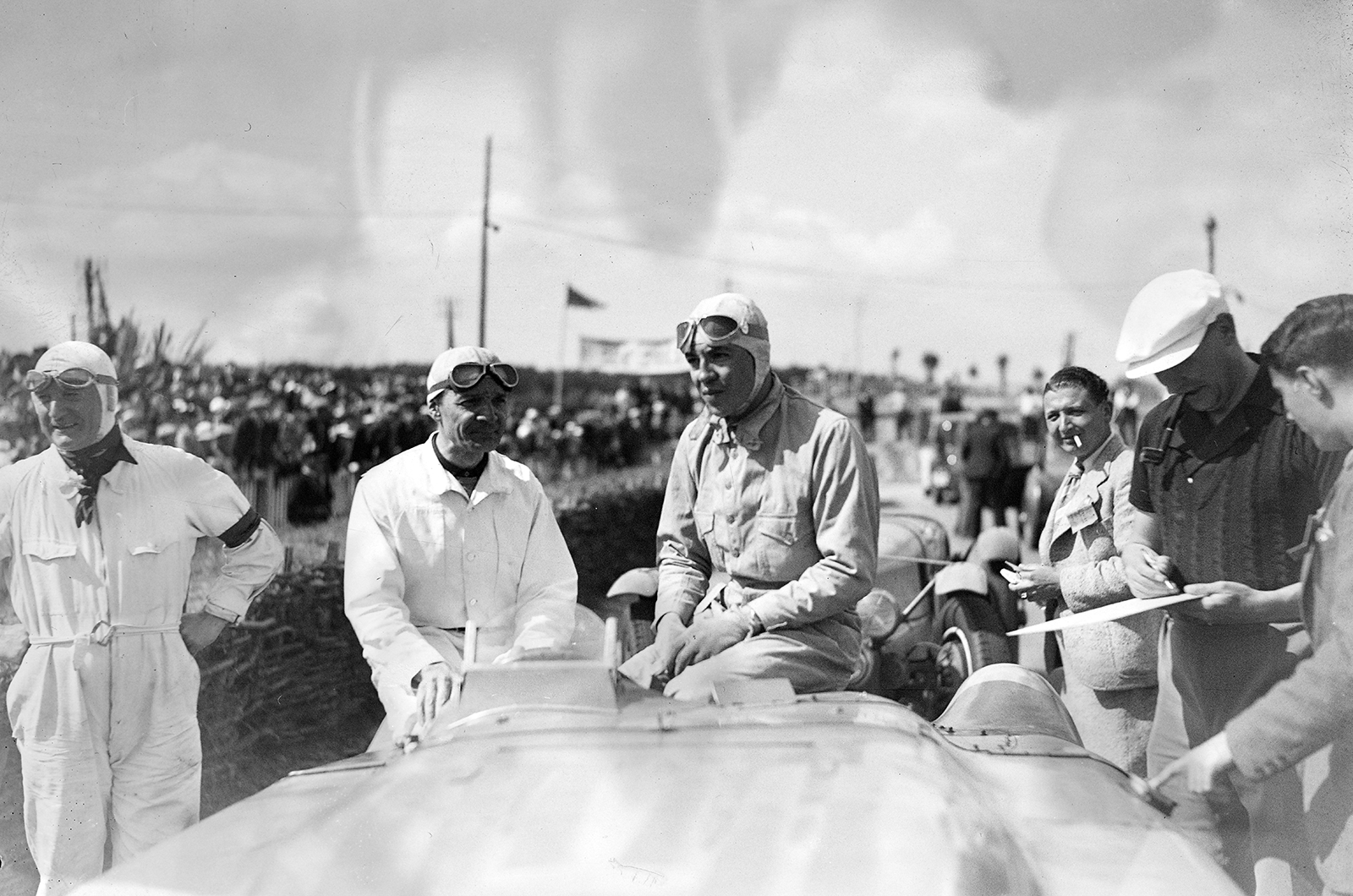

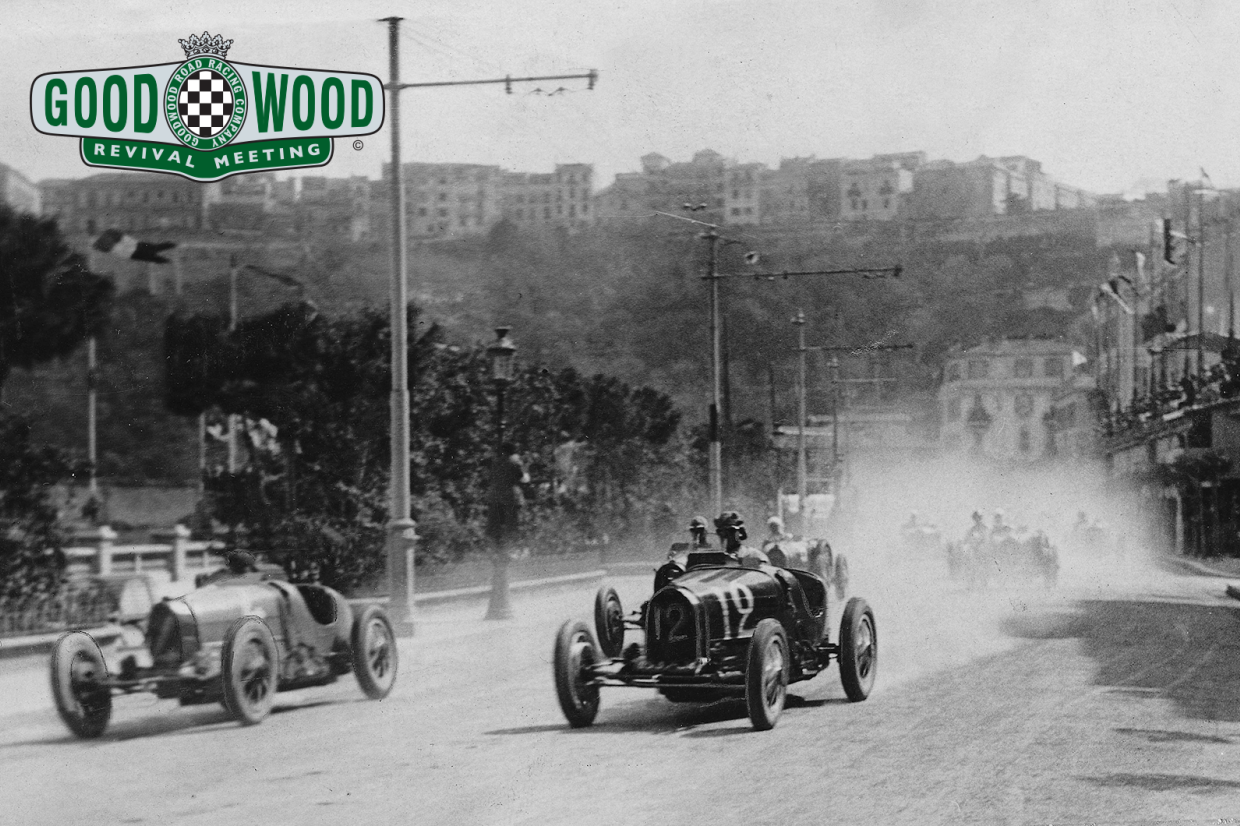

Eventually a lieutenant in the engineering section of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, there he linked up with his Monte-Carlo teammate Lt Colonel Garrad.

Sammy Davis prepares for the 1926 24 Hours of Le Mans; he crashed in the final half hour chasing second, when fading brakes sent him into a sandbank