Push the AC to its limits and you’ll quickly be reminded that you are not, in fact, an endurance-racing legend.

While the talented and brave reported in period tests the ability to ‘use more throttle to keep the tail in check’, a hair-raising twitch is enough to make lesser mortals ease off.

Early Cobra brochures described such comforts as ‘a full instrument panel’, and as you contort your left leg past the enormous transmission tunnel and on to the clutch pedal for another change, the irony isn’t lost.

‘Early Cobra brochures described such comforts as “a full instrument panel”, but it’s far from a comfort in reality’

In this car you work around the machine in many ways, and in harmony in others: the short-throw, direct change of the Borg-Warner T-10 ’box is a delight and the steering, of the revised rack-and-pinion type, is perfectly weighted when matched with the lighter small-block motor.

The leaf-sprung Cobra was always an effective yet slightly crude device in comparison with European sports cars; like using a hammer to drive a screw.

This is a more considered machine, as bouncy and choppy as befits a roadster born in the mid-’60s, but at the same time boasting a compliance that blunts the worst characteristics of the earlier Cobra while accentuating the best.

The 289 Sports is lighter, better balanced and more wieldy than the more powerful 427

It lacks the outright power of the fearsome 427, but the 289 Sports is lighter, better balanced and more wieldy; you don’t need bulging forearms to pull it into line or haul it back from the brink.

Period reports cast some doubt on whether it could be used as a 20,000-miles-a-year everyday car, but simply asking the question highlights the sheer usability of this last-of-the-line small-block wonder.

The more time you spend with it, the better it gets.

Images: Will Williams

Thanks to The Classic Motor Hub

Factfile

AC 289 Sports

- Sold/number built 1967-’69/27

- Construction twin-tube cross-braced steel chassis, aluminium body

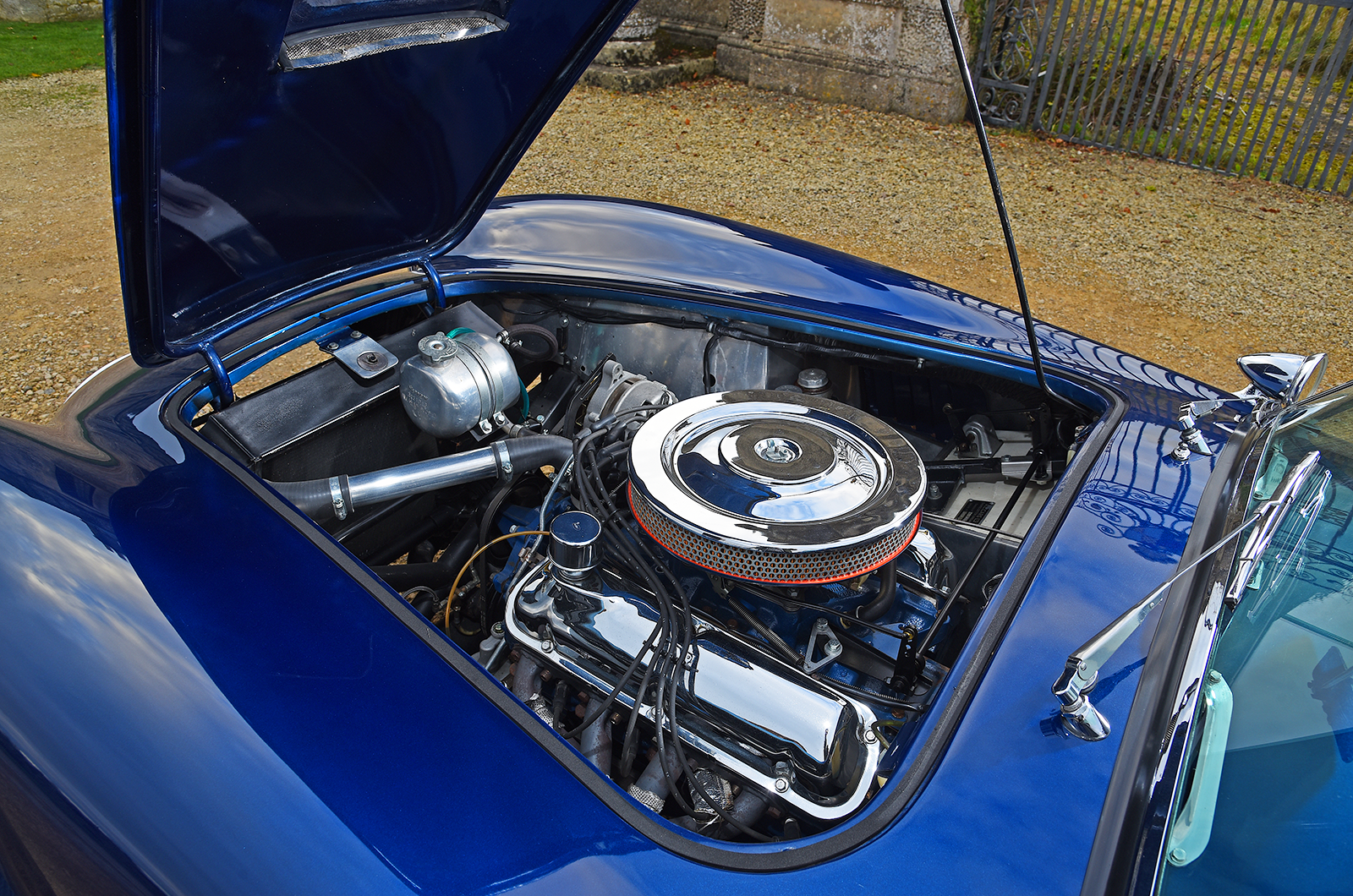

- Engine all-iron, ohv 4727cc V8 with four-barrel carburettor

- Max power 271bhp @ 6000rpm

- Max torque 312lb ft @ 3400rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual with Salisbury limited-slip differential, RWD

- Suspension independent, by double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers f/r; rear trailing arms

- Steering rack and pinion

- Brakes discs

- Length 13ft 3¾in (4057mm)

- Width 5ft 5in (1651mm)

- Height 4ft ¾in (1238mm)

- Wheelbase 7ft 6in (2286mm)

- Weight 2094Ib (950kg)

- 0-60mph 5.6 secs

- Top speed 135mph

- Mpg 17

- Price new £2951

- Price now £4-500,000+*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

READ MORE

Not so mellow yellow: driving the ‘Hairy Canary’ Cobra

AC 428: a Cobra for the jet set

Six of the best: AC Greyhound vs Bristol 406 Zagato

Greg MacLeman

Greg MacLeman is a contributor to and former Features Editor of Classic & Sports Car, and drives a restored and uprated 1974 Triumph 2500TC