Upon inspection, the Hertfordshire-based specialist discovered that this was a remarkable survivor.

Blakeney-Edwards even tracked down the original engine block, number 10402, but it was the car’s history that really captivated the ‘chain gang’ fan.

“The paperwork gave a few clues to the wartime ownership and James’ name,” he recalls.

“Then I found an article in a 1994 copy of Militaria Collector about this courageous young pilot and was gripped by his story.”

Blakeney-Edwards became fascinated with the car’s history and eventually contacted James’ family – they later found old photographs of ‘BMK 102’

Further research, aided by Bradfield, led to contact with James’ family and the discovery of letters and photographs of BMK 102: “It’s an amazing story and we’d love to know more.”

After learning about hero James, Blakeney-Edwards decided that the Nash had to be returned to its authentic specification during the war years.

Work began on stripping the car down to the chassis, with Wayne Fairlie and the team in the firm’s Frazer Nash arm going right through the driveline.

Tudor Summers repaired the timber body frame, wings and panel cracks

“It had always been a good, working car and well looked after,” says Fairlie. “We fitted new bearings, steering, sprockets and brake shoes.”

The timber body frame, wings and panel cracks were repaired by Tudor Summers, but the body was amazingly original – one of the reasons why the car looks so authentic.

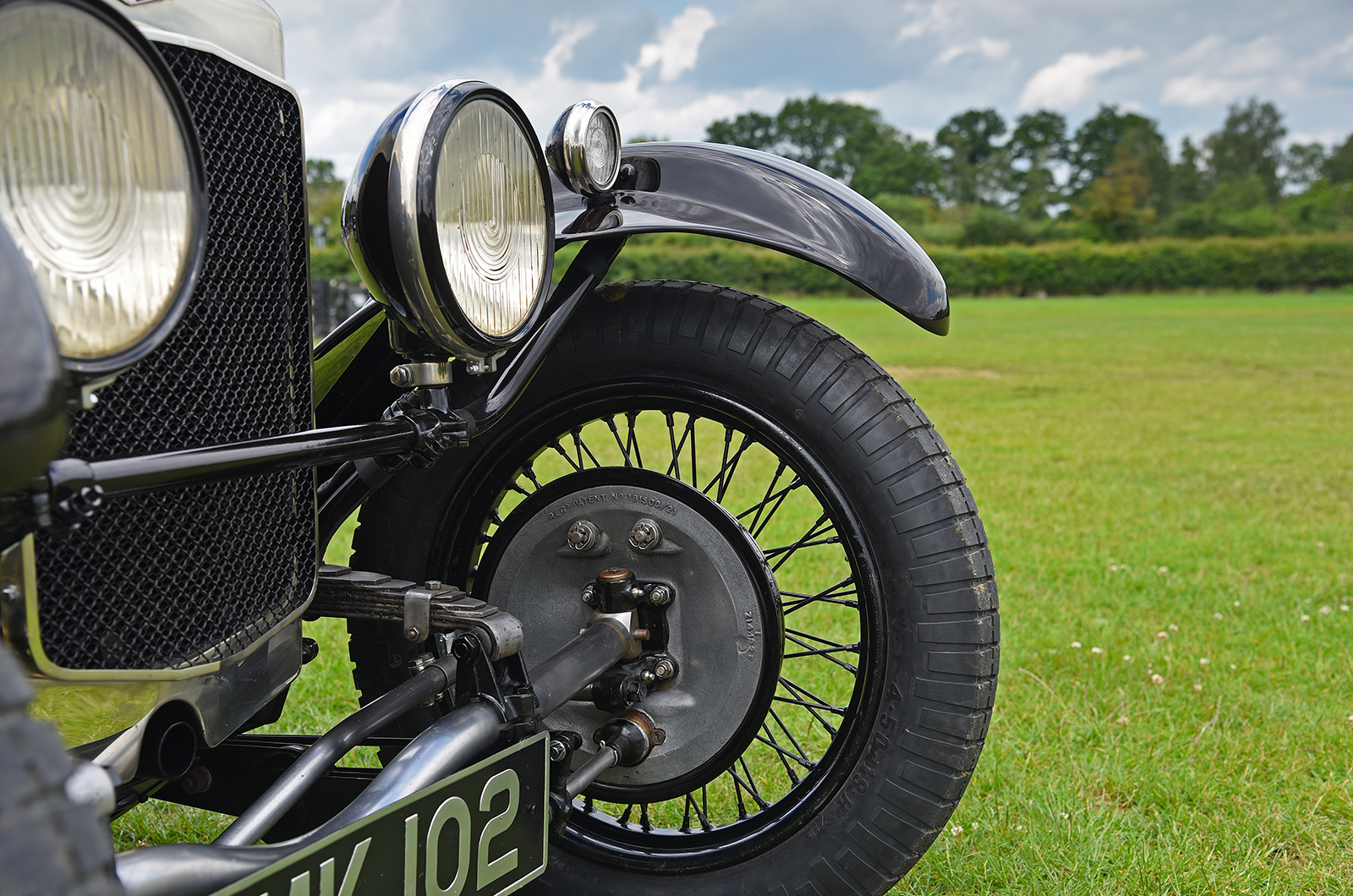

“We didn’t want to make it too perfect and have kept the panel ripples,” says Summers. “All the Bosch lighting is original, and we found some nice factory details such as the advance/retard and hand-throttle levers, the lip to the ’screen frame and the odd-shaped gearlever.”

The Frazer Nash’s distinctive front suspension set-up with a solid axle and inverted quarter-elliptic springs

A fresh Meadows unit was built by Josh Pitts and Jack Parry, which when running-in on the dyno delivered 111bhp at 6050rpm and maximum torque of 108lb ft at 5000rpm, with a 9.65:1 compression ratio.

Early on, the decision was made to return ‘Freddie’ to its original two-tone colour scheme and Blakeney-Edwards went to great lengths to choose the right match.

To enhance the finish, it was also decided to nickel-plate the brightwork – although not the authentic Falcon Works finish, it looks fabulous.

The restored interior and exterior’s Art Deco style is a suitable celebration of the jazz-age era

The final touch was a retrim in ‘pull-up leather’, which has a rich, natural finish that further enhances the car’s style, and the addition of a Smiths aviation clock.

Rolled out into the daylight, ‘Freddie’ looks magnificent, the ivory body and brown wings giving the TT Replica a raffish, Art Deco style that celebrates the jazz-age era.

But the best news of all is that it drives as well as it looks.

The Frazer Nash TT Replica represents one of last production sports cars with an outside gearlever

My test run demands an appropriate location to celebrate wartime owner James.

With no surviving Hampdens or flying Typhoons, the only option was a Hurricane and the wonderful Shuttleworth Collection agreed to roll out its rare 1941 Mk1 Z7015 for photography.

With its 1030hp Merlin V12 engine, this 296mph beauty is the earliest airworthy survivor and a regular star of flying days at Shuttleworth.

The 30-mile round trip also passes RAF Henlow, which dates back to 1918 and during WW2 was used to assemble Hurricanes built in Canada.

The eager four-cylinder engine sounds more sporty high in the rev range

The drive proves a perfect test for the freshly finished TT Replica, with good straights and plenty of roundabouts, while the last scenic miles through Bedfordshire woodland and the idyllic Old Warden village offers timewarp rural views down the long bonnet.

I’ve been going to Shuttleworth since I was a child, and it remains one of my favourite places on earth.

No other pre-war car compares to a Nash, particularly one as sorted as BMK 102.

With only a passenger door, the best route to slide under the broad, four-spoke wheel and on to the flat seat is from the left.

The fresh Meadows unit was built by Josh Pitts and Jack Parry

The gruff exhaust of the eager ‘four’ doesn’t sound very sporty until it starts to sing higher in the rev range.

At first, the crab-tracked chassis layout feels and looks strange, particularly if you’re following.

The brakes pull to the left when cold, and into corners it initially wants to understeer, but once everything is warmed up and you’re in the ‘chain gang’ groove, its character is addictive.

Once warm, the Frazer Nash’s brakes pull straight and strong

The gate of one of the last production sports cars with an outside gearlever is unusual, with first away and forward.

The change is super-fast and, once out of first, the cogs can be selected without using the clutch. The faster you go, the slicker the change.

The high-geared steering is light, and once up to speed barely requires any movement as the throttle commands the direction.

‘Blakeney-Edwards says I didn’t rev high enough and takes me for a mindblowing blast, where no modern can catch us’

Empty roundabouts are great fun, and en route I can’t resist a couple of circuits to slide the tail.

Both Blakeney-Edwards and Fairlie rate BMK 102’s handling and ride because there’s no match for the metallurgy of an original chassis, which flexes just the right amount.

The brakes pull straight and strong once warm, and the engine revs through the range with heaps of torque, like no Meadows I’ve experienced.

The car’s new owner plans a road trip across France to visit ‘Jimmie’ James’ final resting place

Back at the workshop, Blakeney-Edwards maintains that I didn’t rev it high enough and takes me out for a mindblowing blast down the London Road, where no modern can catch us.

The lucky new owner has been supportive of the restoration route and is just as enthusiastic as the team about BMK 102’s history.

There’s already talk of a road trip across France to visit ‘Jimmie’ James’ final resting place in Evreux. I’m not one for graveyards, but prefer to celebrate a hero by experiencing a car or place they were connected to.

That memorable drive in James’ restored Nash to Old Warden and getting to sit in a Hurricane was the perfect way to commemorate his short, courageous life.

Images: Will Williams

Thanks to: Peter Bradfield; Blakeney Motorsport; the Shuttleworth Collection

READ MORE

Aston Martin DB3: foundation for success

Raising the saloon bar: Frazer Nash-BMW 326

Unique Bentley T-type Special: Crewe cut

Mick Walsh

Mick Walsh is Classic & Sports Car’s International Editor