It wouldn’t be the only one: chassis numbers were dot-punched and later stamped into the split-axle pivot and could be eroded by rust, accident damage or welded-on towing eyes.

Postan is comfortable with the car’s status and has no plans to register it, but points out that it came into existence more than likely in the way that many of them did: “It’s an old chassis, but we don’t know where from.

“It has been suggested that this frame was constructed out of the remains of one that was cut up and stuffed into a garage pit in Nottingham in the late ’60s.”

This car’s build made real progress in lockdown

He continues: “As an art dealer, my interest has always been in the growth of Modernism and new ideas in Britain.

“The art film-maker Tony Halton, researching for his next film, made contact – it turned out that he was amazed to find that I was still alive, and as a petrolhead he became a chum.

“He’d been collecting the parts to build a Six, but he was moving and one of his projects had to go.”

“It was a much bigger task than I expected”

“I’d finished my 30-year Lamborghini Jarama rebuild,” he goes on, “having sold my Lotus Cortina to fund it, so to fill the empty space in the garage the Six moved from Folkestone to Oxfordshire.

“I thought it would be an easy assembly job, but it came in a van as a heap of parts and was a much bigger task than I expected.

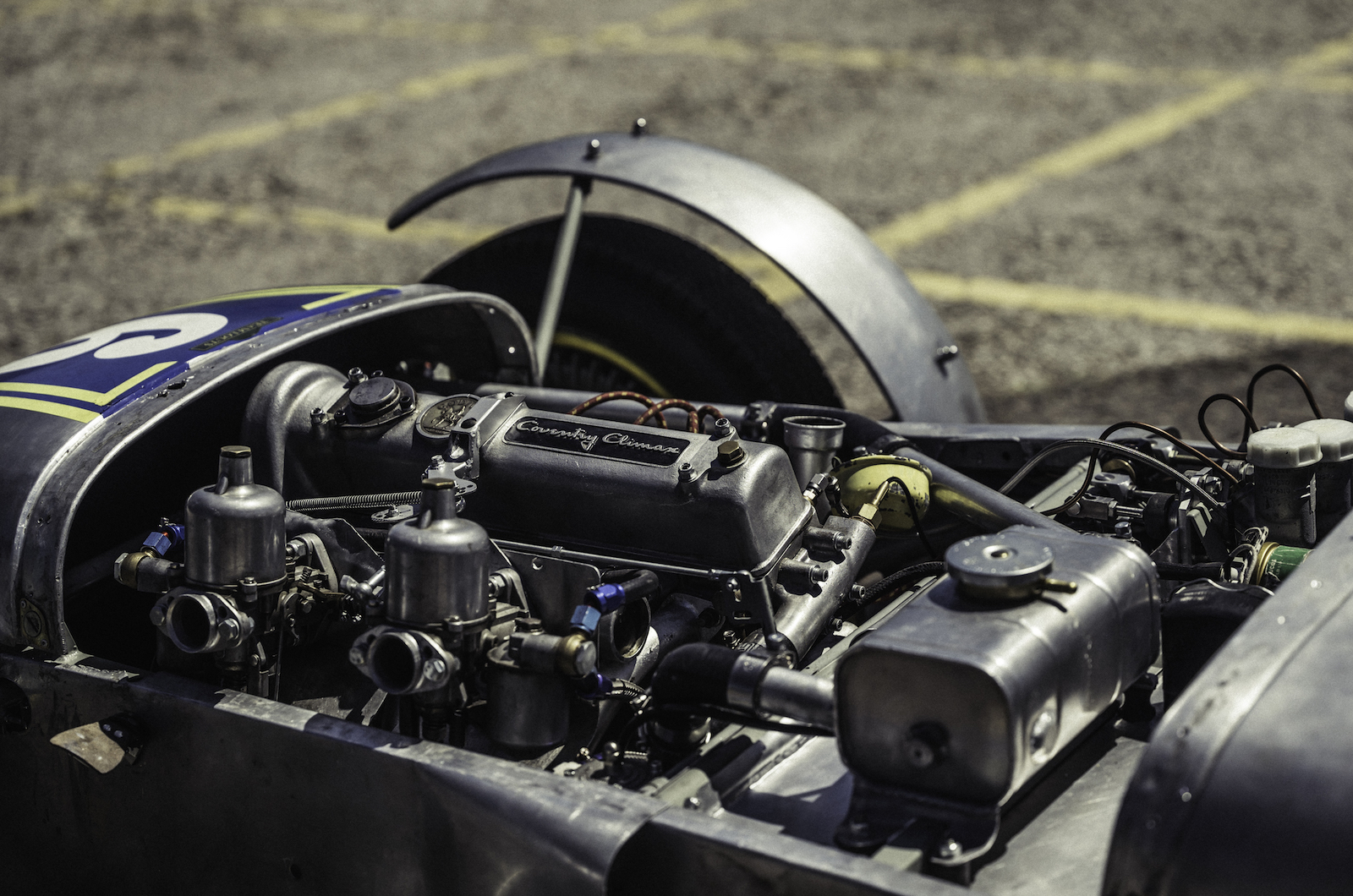

“Lockdown helped me. I found an early engine of the right sort of period and had it built by Tony Mantle of Climax Engine Services.”

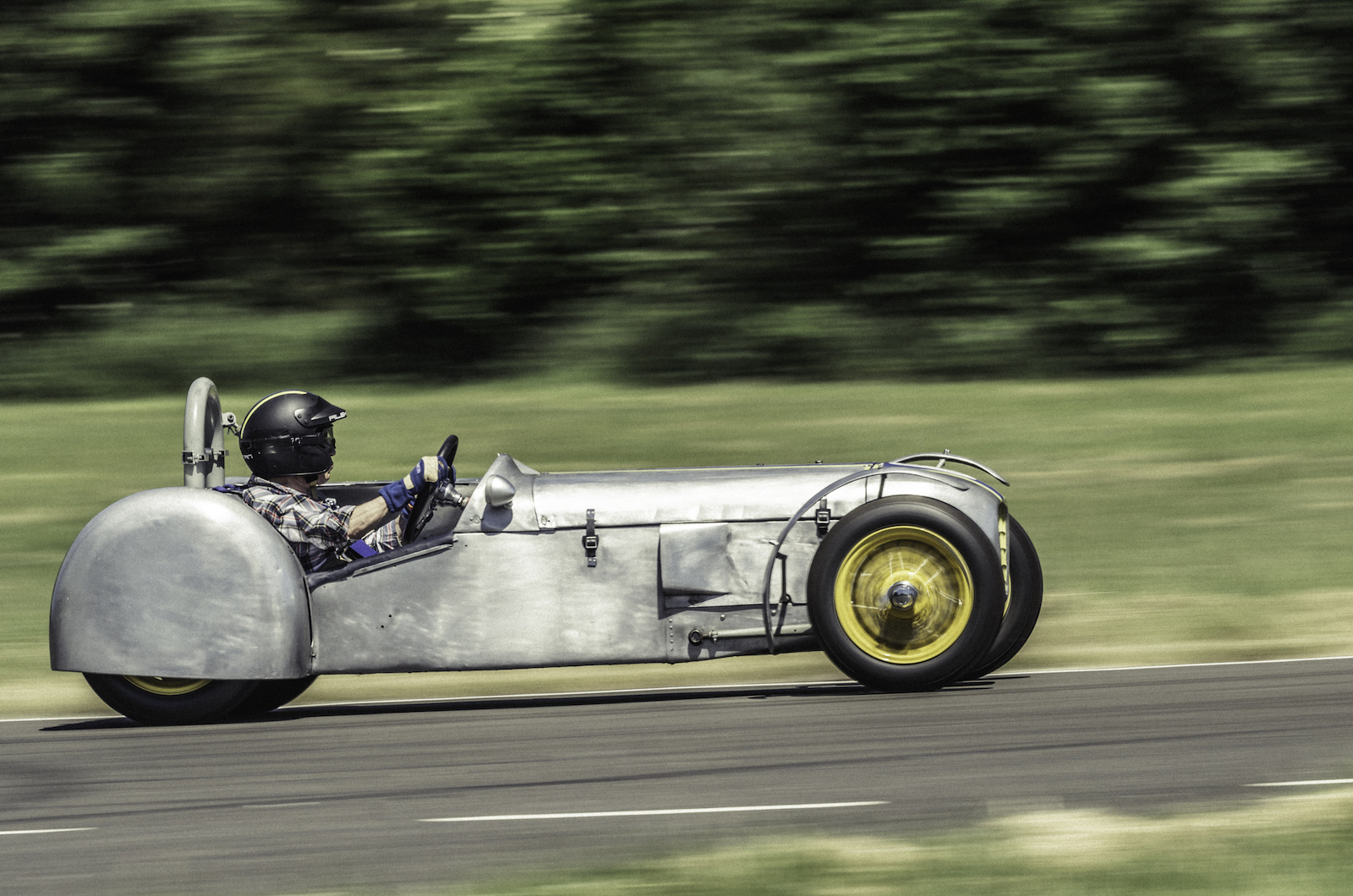

Owner Alex Postan did a lot of the work to this Lotus Six himself – with impressive results

“The Austin A30 ’box has Sprite internals and the brakes came from Mike Brotherwood,” Postan explains.

“The bodywork, built by Len Pritchard of Williams & Pritchard, was originally on [the famous Lotus Six] UPE 9.

“I made the transmission tunnel, the bulkhead and the aluminium tonneau cover, plus the fuel system.”

Radial-finned drums are aluminium copies – the coil-overs aren’t period

Postan finishes: “It’s on 60-spoke wire wheels; I’ve got some 48s, but these are stiffer.”

Too stiff, perhaps.

This car is more than the sum of its parts, which all work beautifully together. Too well, maybe.

True to Lotus form, during our drive, something eventually broke.

There isn’t enough power for showy slides, but a gentle rearward bias on the throttle helps to nudge the tail wide

This was essentially a post-rebuild shakedown session, but after about 30 laps of giving it a mild to enthusiastic seeing to, a rear-axle bearing let go, allowing the wheel to flap around, which, on such a keenly focused chassis, was instantly detectable.

But it stayed on the car and brought the driver home – in Chapman’s world, that probably would have counted as a result.

Images: Olgun Kordal

READ MORE

Garage greatness: a homemade ode to a golden Grand Prix era

15 times Lotus got it just right

Maserati Shamal: the best of the biturbos

Paul Hardiman

Paul Hardiman is a regular contributor to – and former Deputy Editor of – Classic & Sports Car