There is very little road noise and it has a solidly comfortable ride on its 16in crossply tyres, which make the steering weave slightly at anything above 50mph. On radials the steering would probably be unacceptably heavy; as it is, ’50s-style wheel-feeding is the order of the day at low speeds.

To its credit it is not a sloppy, wallowy car as such, but rough handling doesn’t seem appropriate for an old lady that has been cherished for almost seven decades now.

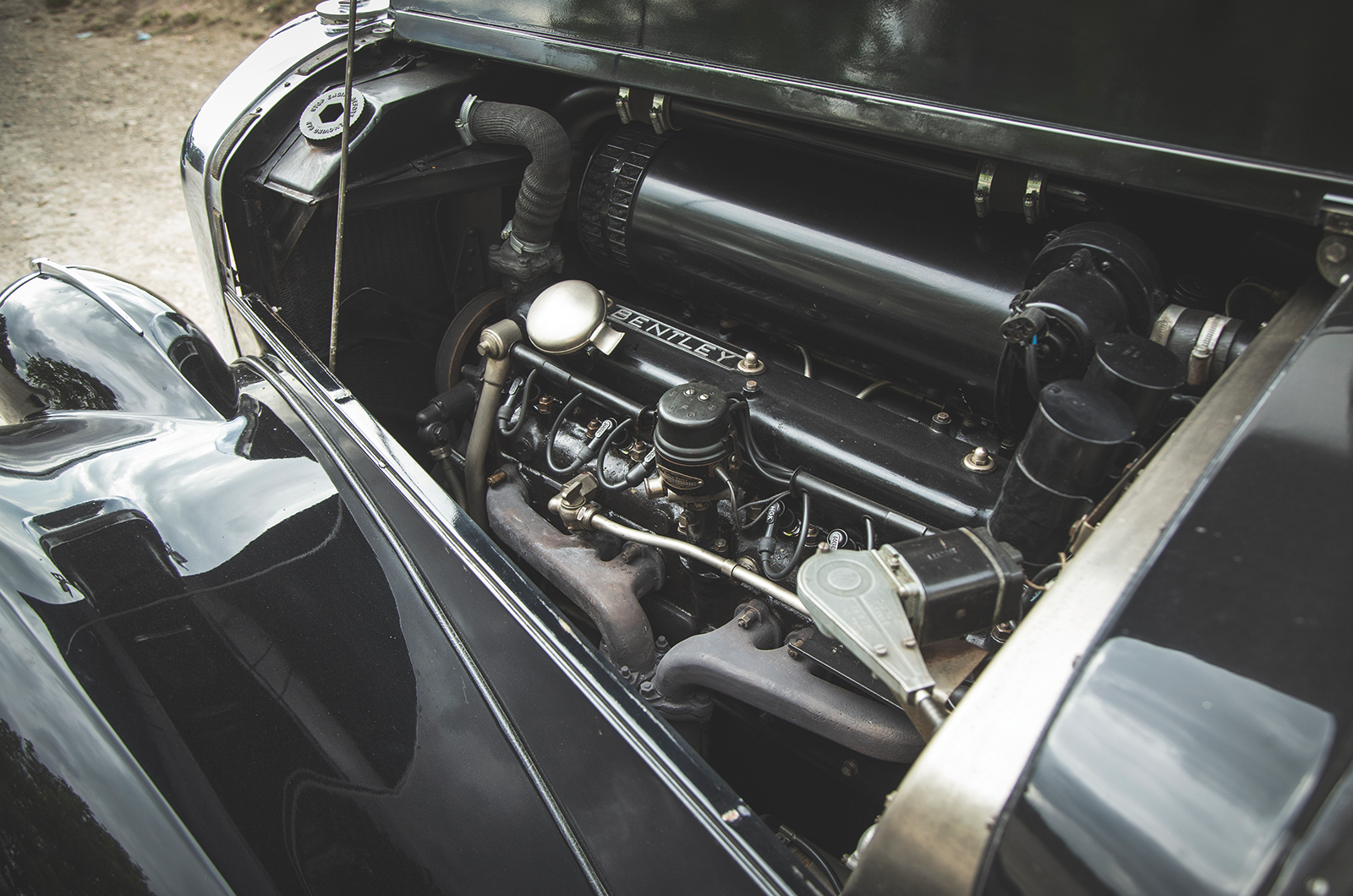

Bentley was close-lipped with its performance figures in period

The Bentley feels a more assertive vehicle, with more ‘margin’ built in, and its big engine is both smoother and brawnier than the Armstrong’s.

It will glide you along with limousine refinement at low speeds or urge you up into the 80s and beyond as a natural cruising gait. In fact, it would give you 80mph+ in third gear.

It romps along with torque everywhere, the only pity being that you have less excuse to handle the mechanically delightful right-handed change.

Although similarly geared, the action of the Bentley’s steering is silkier and more positive than the Armstrong’s and the car will negotiate a smooth, twisty road at a rate that defies its matronly bearing.

Only steering kickback, and a lack of friction between backside and seat, mar the driving experience.

Both cars are about atmosphere and ambience; the aroma of the leather, the views out along their bonnets and the patina of originality.

Their size and weight give them a mechanical physicality to drive that would not endear them to anybody as modern shopping cars, but they were never about that.

The MkVI is happy to cruise or to push on

Even now you can see how these cars eased the anxieties of those wealthy ’50s motorists who could afford to buy in to the sort of refinement that made long journeys shorter and less fatiguing.

This pair offered speed and civility of an order beyond most people’s experience, and a level of general superiority over the average tin box that you cannot duplicate today.

For the man for whom time really was money, cars such as these were almost an essential of business life that made long trips to a board meeting or building site a pleasure rather than a chore.

Today, both represent good value at a wide range of prices, the Bentley in particular surviving in large numbers despite the rusty reputation of its Pressed Steel-supplied body.

Siddeleys, on the other hand, are thinner on the ground but still out there, supported by an excellent club and surprisingly good spares supply.

Coming up with a figure that would part Hughes from these two is a different game. Both cars have their price but are not actively for sale, primarily because Hughes has to be sure they go to the right sort of customer.

He talked the Bentley’s last suitor out of a deal when it turned out it was going to be used for long-distance rallying (a criminal thing to subject a car such as this to when there are so many much less specimen examples available) and is very anxious that the Armstrong, perhaps the lowest-mileage and most original of its type anywhere, stays that way.

Who knows, as saloons such as these become increasingly rare, especially in such as-new condition, is the era of the classic-car preservation order almost upon us?

Images: Luc Lacey

This feature was originally published in our October 2019 issue

Factfiles

Armstrong Siddeley 3.4/346

- Sold/no built 1953-’59/7680 (all)

- Construction steel body, steel chassis

- Engine all-iron, ohv 3453cc straight-six, with single carburettor

- Max power 125bhp @ 4200rpm

- Max torque 177Ib ft @ 2000rpm

- Transmission four-speed auto, preselector or manual, driving rear wheels

- Suspension: front independent, by coil springs and wishbones rear live axle, half-elliptic leaf springs; telescopic dampers, antiroll bar f/r

- Steering recirculating ball

- Brakes drums (with servo from Mk2)

- Length 16ft 1in (4902mm)

- Width 6ft (1830mm)

- Height 5ft 2¼in (1600mm)

- Wheelbase 9ft 5in (2896mm)

- Weight 3472Ib (1575kg)

- 0-60mph 15.5 secs (manual)

- Top speed 91mph

- Mpg 17-20

- Price new £1728 (1953)

- Price now £9-19,000*

Bentley MkVI

- Sold/no built 1946-’52/5201

- Construction steel chassis, Pressed Steel body

- Engine iron-block, alloy-head, inlet-over-exhaust 4257cc straight-six (4566cc from mid-’51), twin SU HD4 (H6) carburettors

- Max power not disclosed

- Max torque not disclosed

- Transmission four-speed, three-synchro manual or Hydramatic four-speed auto with fluid coupling, driving rear wheels

- Suspension: front independent, by double wishbones, coil springs rear live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs; lever-arm dampers f/r

- Steering cam and roller

- Brakes drums all round, hydraulic at front, with mechanical servo

- Length 15ft 11½in (4864mm)

- Width 5ft 9in (1753mm)

- Height 5ft 4½in (1638mm)

- Wheelbase 10ft (2743mm)

- Weight 3954lb (1793kg)

- Mpg 17

- 0-60mph 15.2 secs

- Top speed 100mph

- Price new £2997 (’46)

- Price now £17-40,000*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

READ MORE

Bentley’s heartbeat: the first and last L-series V8s

Troubled succession: Lancia Aurelia and Lancia Flaminia

Transatlantic hybrids: Bristol 407, Jensen C-V8 and Gordon-Keeble GK1

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car