The rest is history, as they say, and Wolseley went on to become a dominant force in motoring’s Edwardian era.

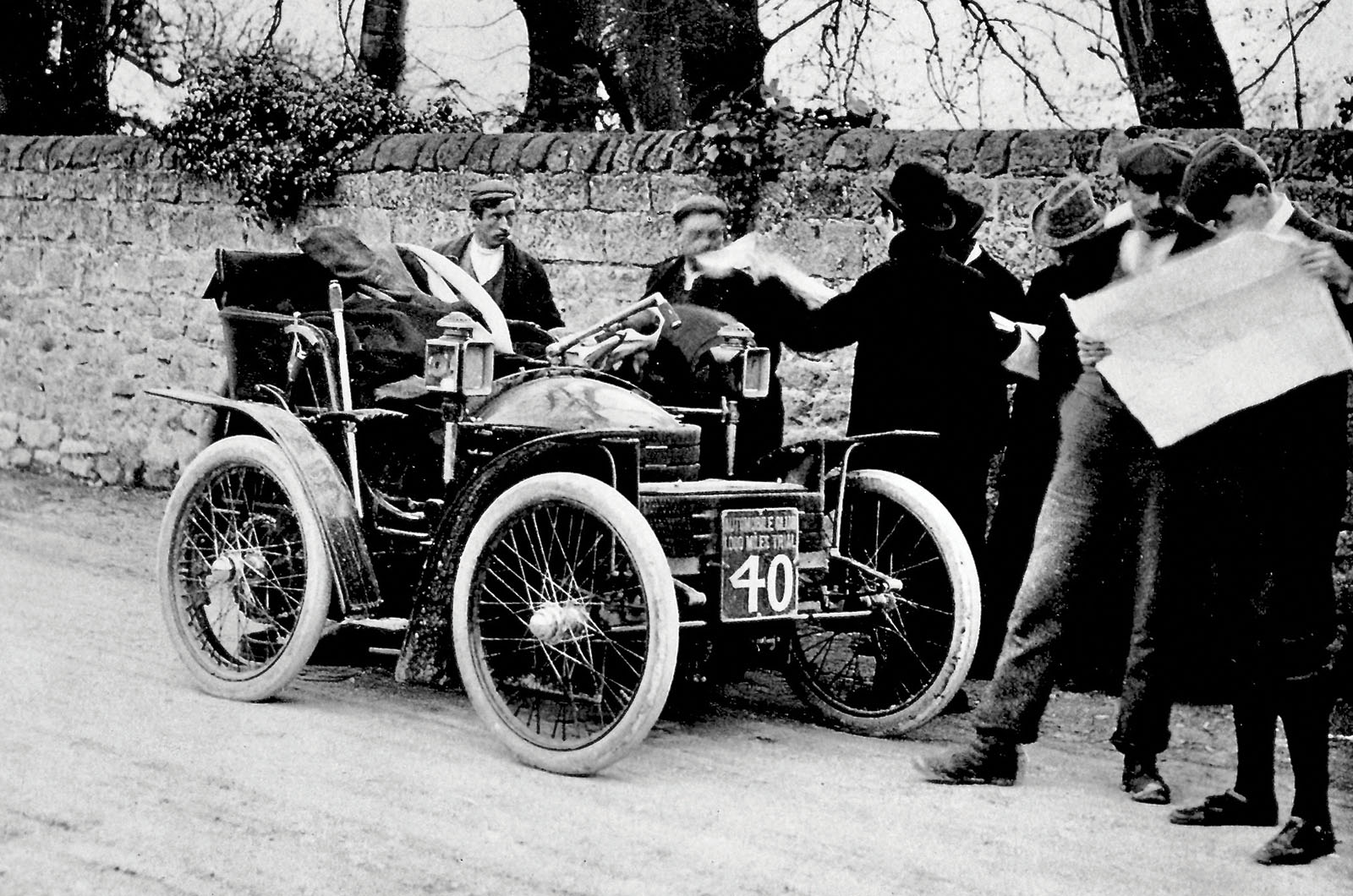

Smooth surfaces today, but the 3.5bhp Wolseley endured 1000 miles of mostly unpaved roads on its inaugural event, more than 125 years ago

OWL is perhaps not hugely representative of the larger, more prestigious machinery that Wolseley went on to produce in the period leading up to the Great War.

But viewed entirely objectively, it is a remarkably proficient and capable motor car.

Powered by a 1.3-litre engine of Wolseley’s own design, its single cylinder has a 4½in bore and a 5in stroke, with its liner, piston and combustion chamber all cast from iron.

Wolseley was keen to emphasise the construction quality of the engine, with all its components ground to fit, rather than being ‘packed’ (a practice that should be ‘abolished’, it asserted).

The Wolseley 3.5hp Voiturette’s sight-feed lubrication replenishes the constant-loss system

Oil is sent to the bearings through a sight-feed lubricator mounted on the dash, with capacity for, the company claimed, 150 miles of running.

The ignition uses two accumulators and a Blake trembler coil – common with many other early veterans.

The transmission, with chain final drive to the rear wheels, is quite ingenious and, as we soon find, entertaining to use.

The three-speed (plus reverse) gearbox, mounted transversely beneath the bench seat, is moved back and forth as the driver selects different ratios via toothed ‘channels’ in the transmission gate.

The Wolseley’s controls are complex for a veteran car newcomer, but at least the horn is straightforward

When the lever is pulled back into a neutral zone, the gearbox is pushed forward out of the confines of the fabric belt in which its drive is contained; when the lever is pushed ahead into one of the gear channels, the ’box engages progressively with the belt until it’s fully locked in.

The same lever’s lateral throw allows you to select your chosen ratio, with its lower end connected to a mechanism that moves across the ’box to engage the corresponding gear.

Apart from a hand throttle and central steering tiller, OWL’s only other main control is a footbrake operating two shoes acting directly on an additional rim fixed to the inside of each of the car’s spoked 30in rear wheels.

The 1899 Wolseley’s steering tiller isn’t troubled by kickback

Our drive today starts from the British Motor Museum in Gaydon, where OWL has been a resident since 1980.

(Its display history actually goes back to 1912, when it became one of the first exhibits in Britain’s first public car collection, the Motor Museum, aptly founded by the proprietor of The Motor, Edmund Dangerfield.)

OWL’s starting procedure is thus: fuel on; fully retard the ignition on the small, dash-mounted quadrant; set the hand throttle at its mid-point; then move to the nearside front of the car and start to crank – fast, and with some commitment – before switching on the ignition, after which OWL fires immediately. I’ve known worse.

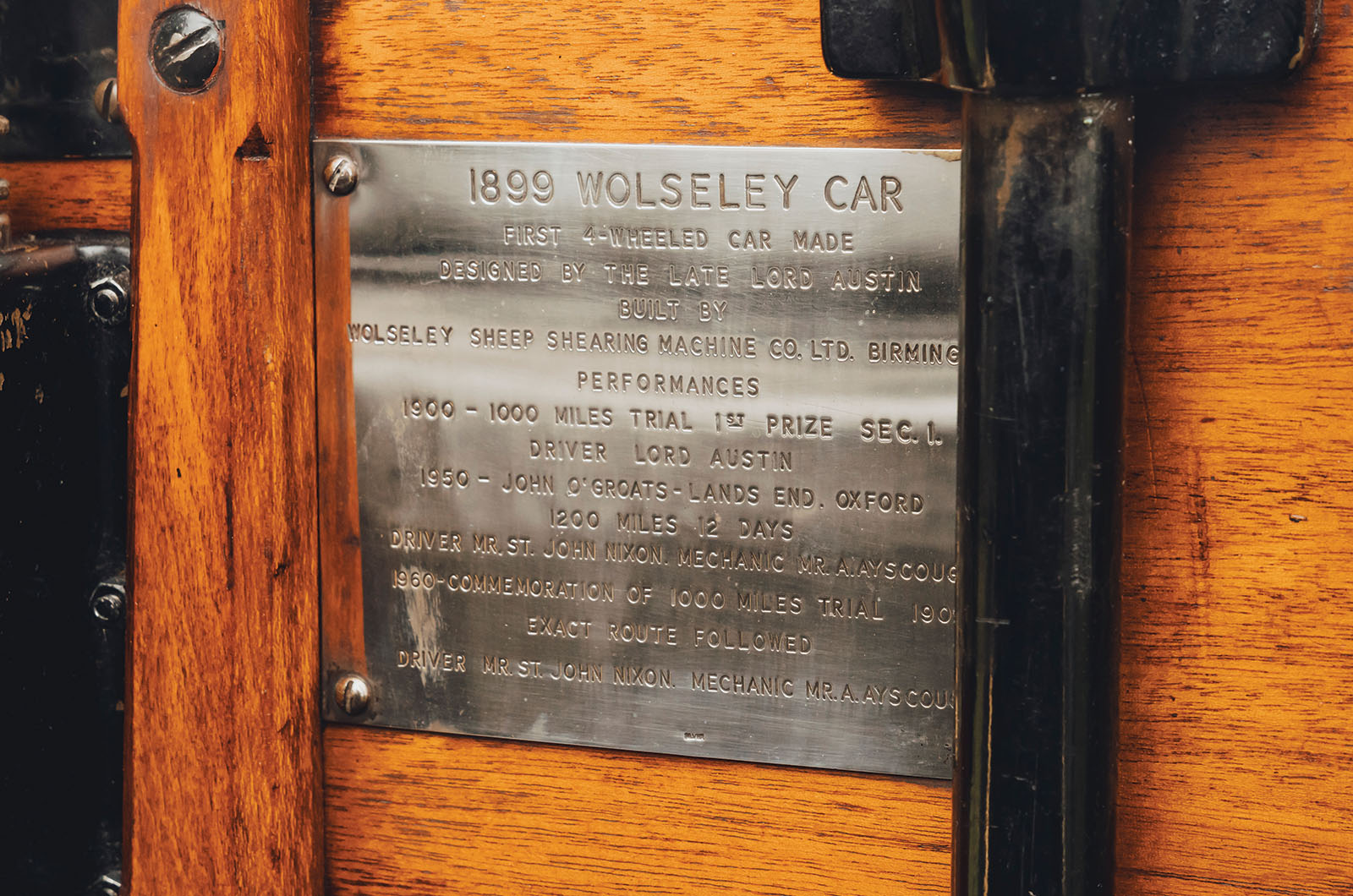

A plaque commemorates this Wolseley’s legacy

There is an art to driving any veteran, and while their control systems vary wildly, the pleasure – for me, anyway – is making steady progress without the need to overexert any componentry; I’m sure Mr Austin would have concurred.

To pull away, you add some ignition advance, leave the throttle in its midway position, release the handbrake and ease the long transmission lever forward in its first gear slot – just enough to attain jogging pace – before making a back-and-forth change into second gear.

The single cylinder’s metronomic thumping intensifies as you push the lever further in its channel.

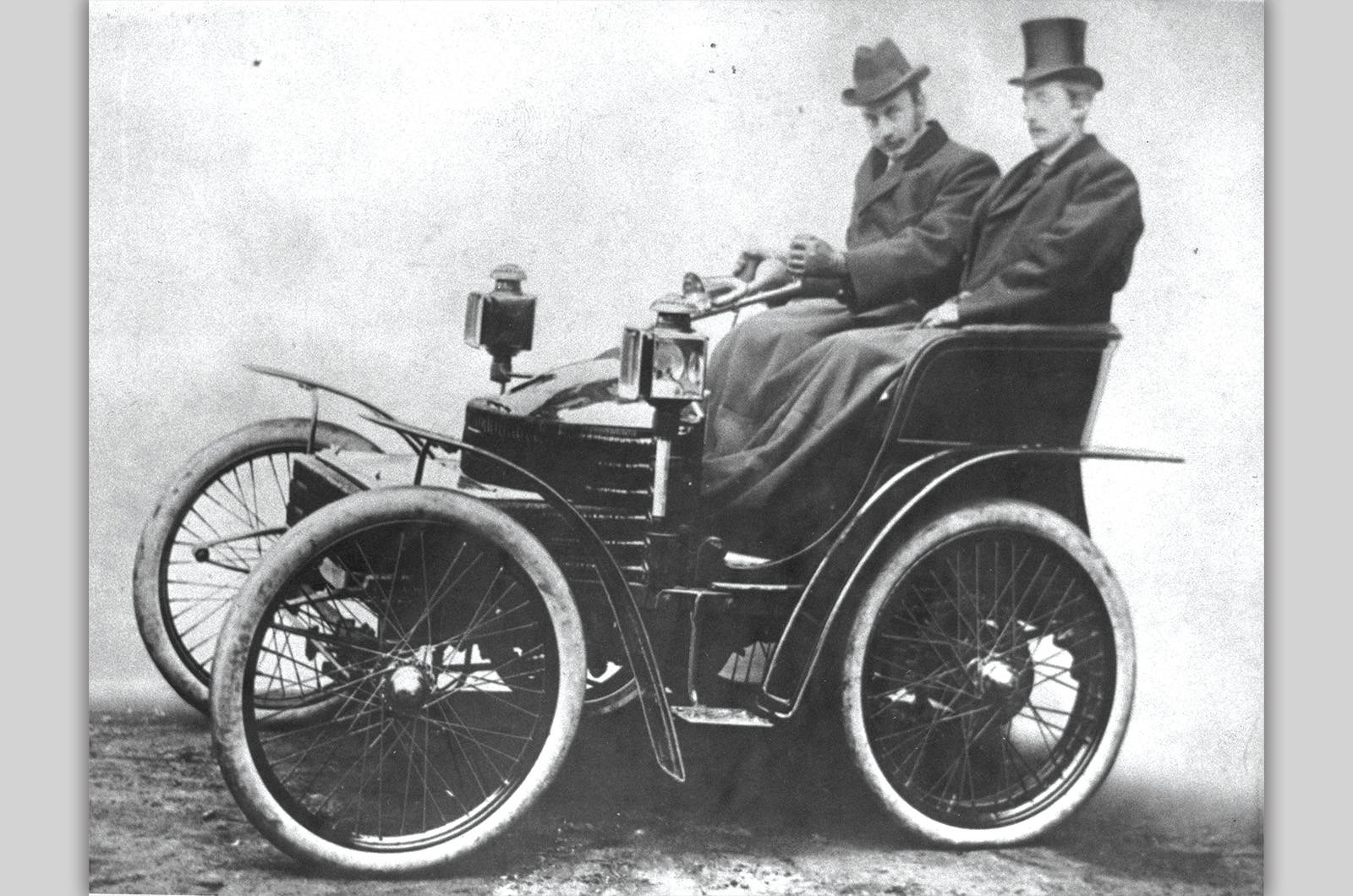

Herbert Austin at the tiller of the Wolseley 3.5hp Voiturette in 1900 © Royal Automobile Club

It’s a highly physical experience for your upper body, because you are in effect forcing the weight of the gearbox against the drive belt to attain more speed.

Once into third, with a clear road before you and the transmission locked in, OWL lopes along, its monobloc engine surely still turning at below 1000rpm.

On paper, a five-years-younger Vauxhall Light Car’s coil-sprung chassis should feel more sophisticated than the Wolseley’s cart-sprung set-up, but once you have acclimatised to OWL’s central steering tiller – benign enough to avoid kickback from potholes and drain covers – its impressive stability licks that of the later, London-built car.

‘This important Wolseley was among a select group of pioneer vehicles that first brought motoring to the masses’

More than that, though, is the sheer thrill of piloting a genuinely driveable car from the century before last.

No motor vehicle engages you quite like an early veteran: the organic simplicity of the engineering is refreshing and, while operational solutions were still diverse, you find yourself sharing their maker’s naïve optimism that their particular way was the future.

The internal-combustion-powered motor car, whatever its form, was the future, though, and 125 years ago a nation of doubters was starting to be convinced.

Images: Max Edleston

Thanks to: Stephen Laing, British Motor Museum; Jonathan Gill, London to Brighton Veteran Car Run

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

Genevieve reunion: meet the Darracq and Spyker film stars

Vauxhall vs KRIT vs SCAT: Edwardian titans do battle

A 25,000-mile adventure in an Austin Seven

Simon Hucknall

Simon Hucknall is a senior contributor to Classic & Sports Car