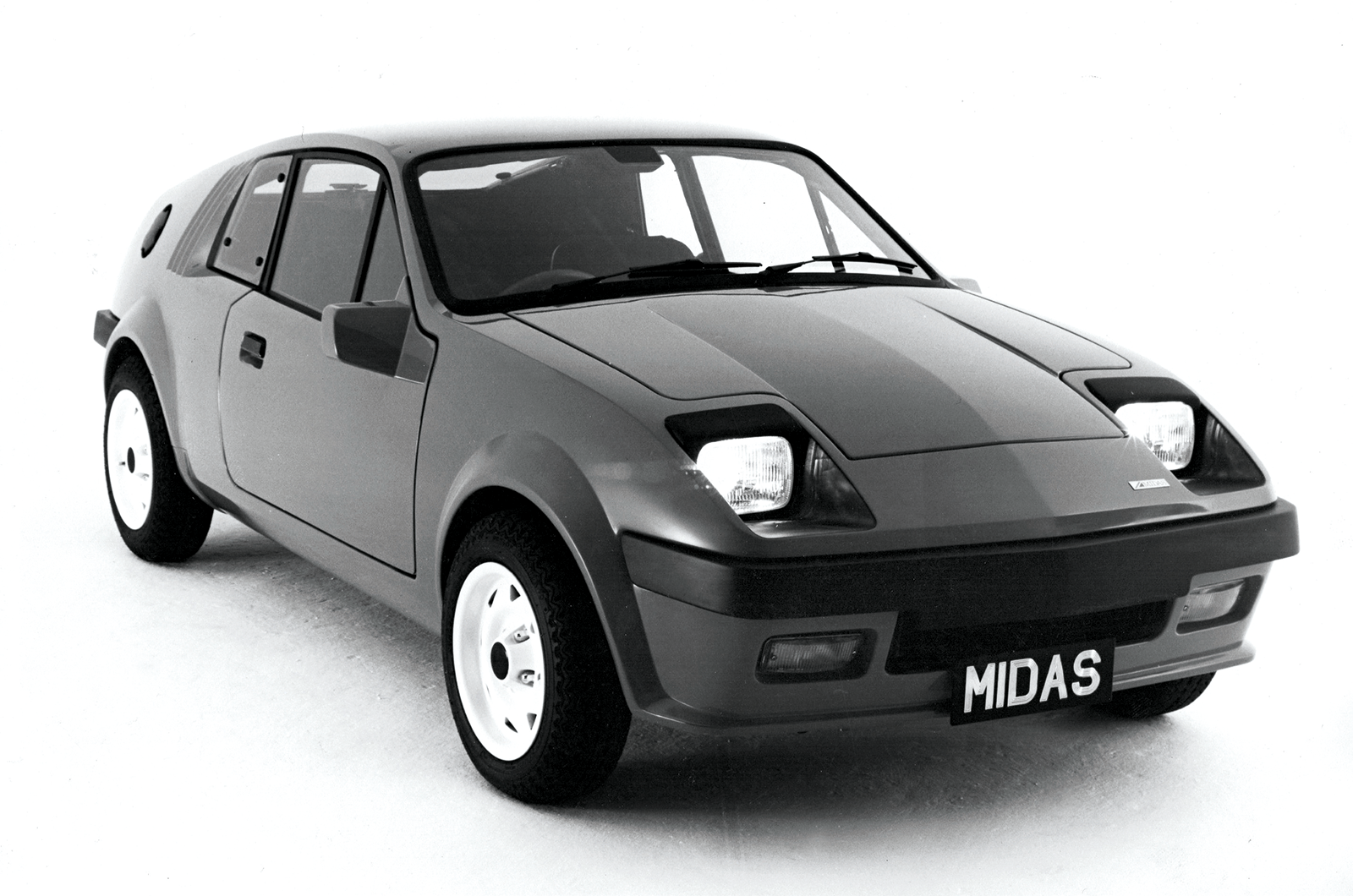

Those who knew where to look would find genuine quality – kits from brands such as Westfield, Sylva and Midas, not to mention Caterham, would go together exactly as described in comprehensive documentation, built by studious customers with well-equipped garages.

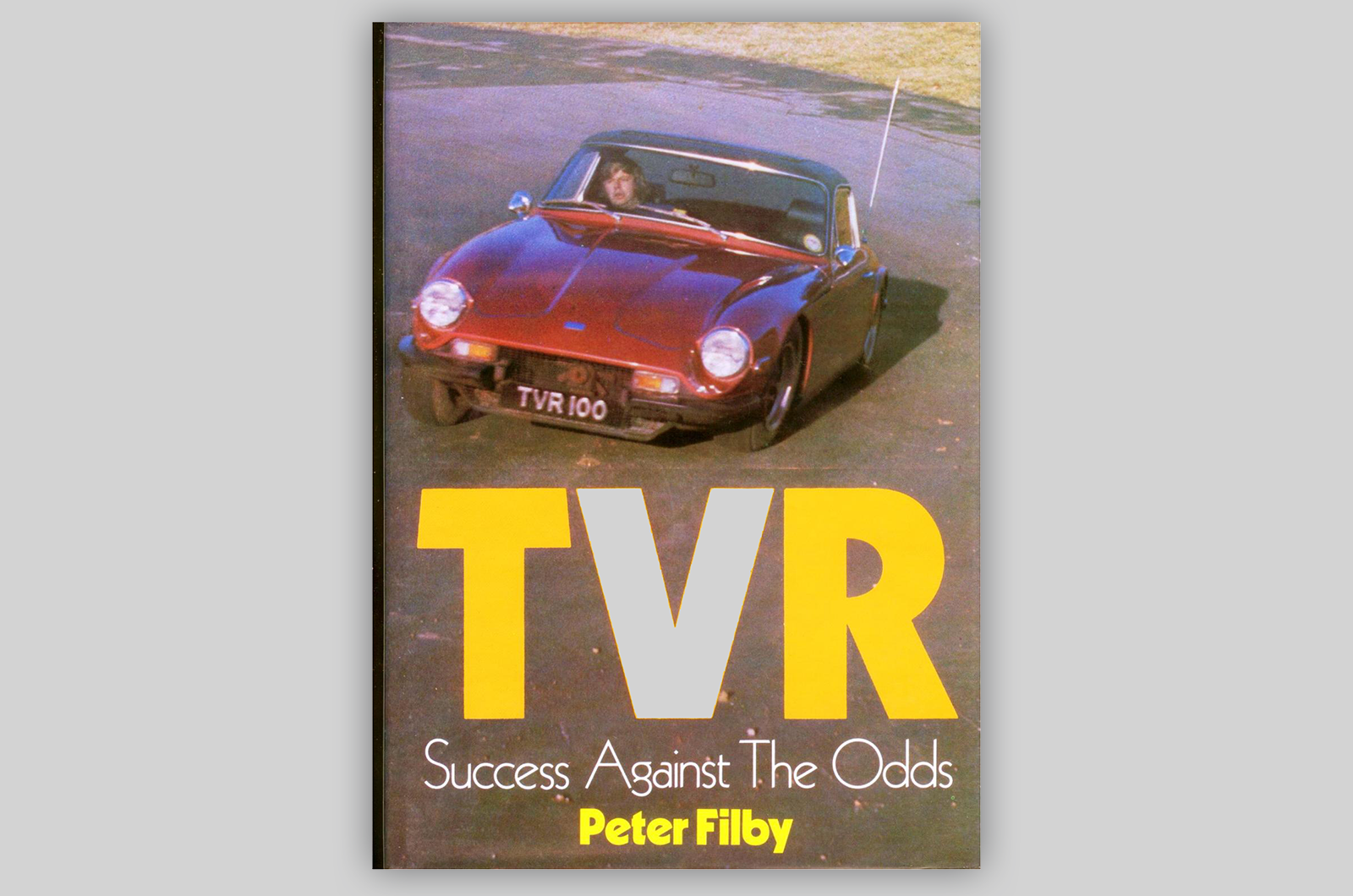

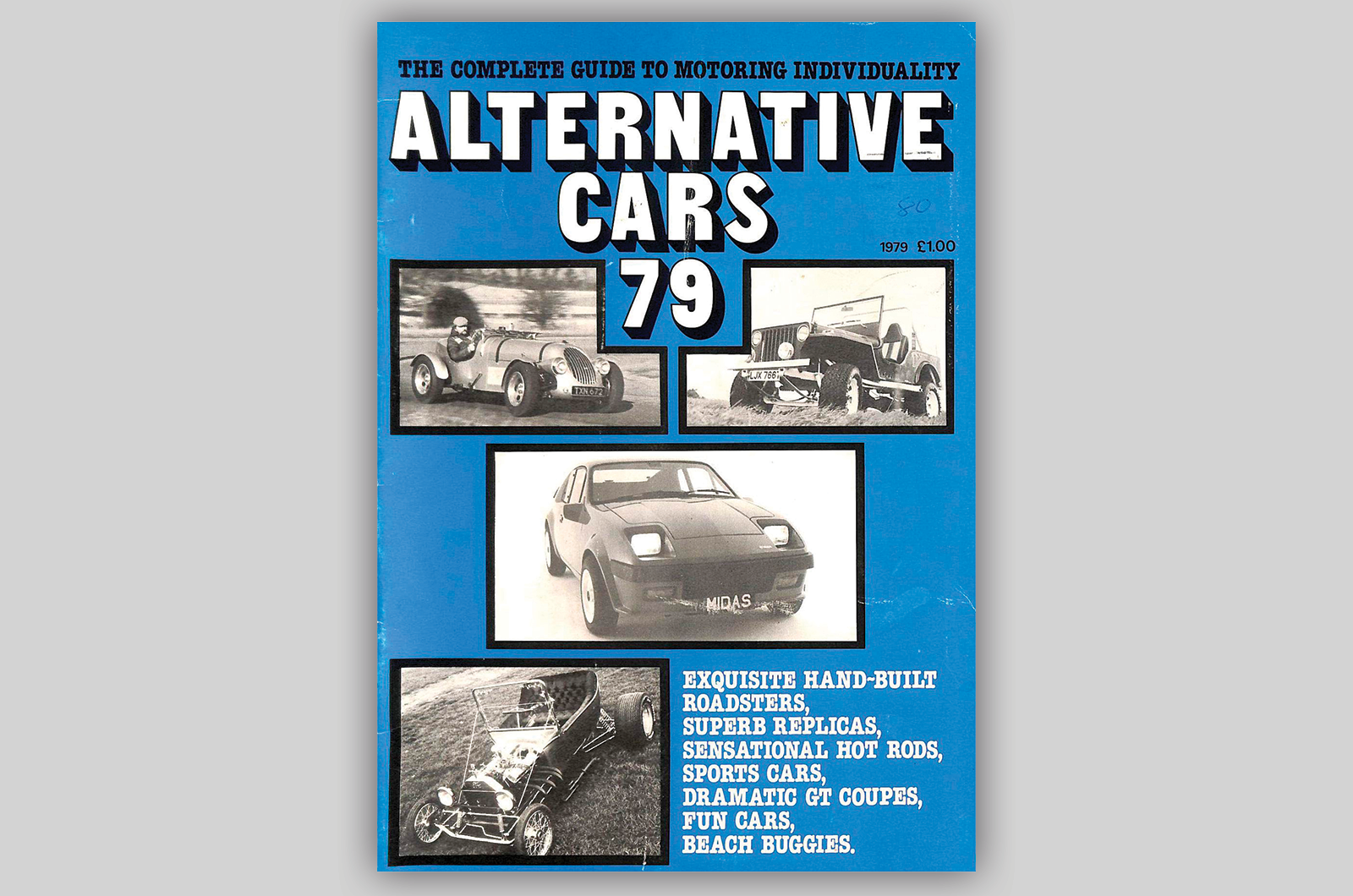

As his adventures with Alternative Cars had already proved, Peter saw these ‘top end’ companies as the bedfellows of low-volume specialist manufacturers such as TVR; the only difference was that the former presented the option to assemble the vehicle yourself.

But production cars had no place in Which Kit?.

‘The wheat of the kit car world was often unfairly dismissed. Those who knew where to look would find genuine quality’

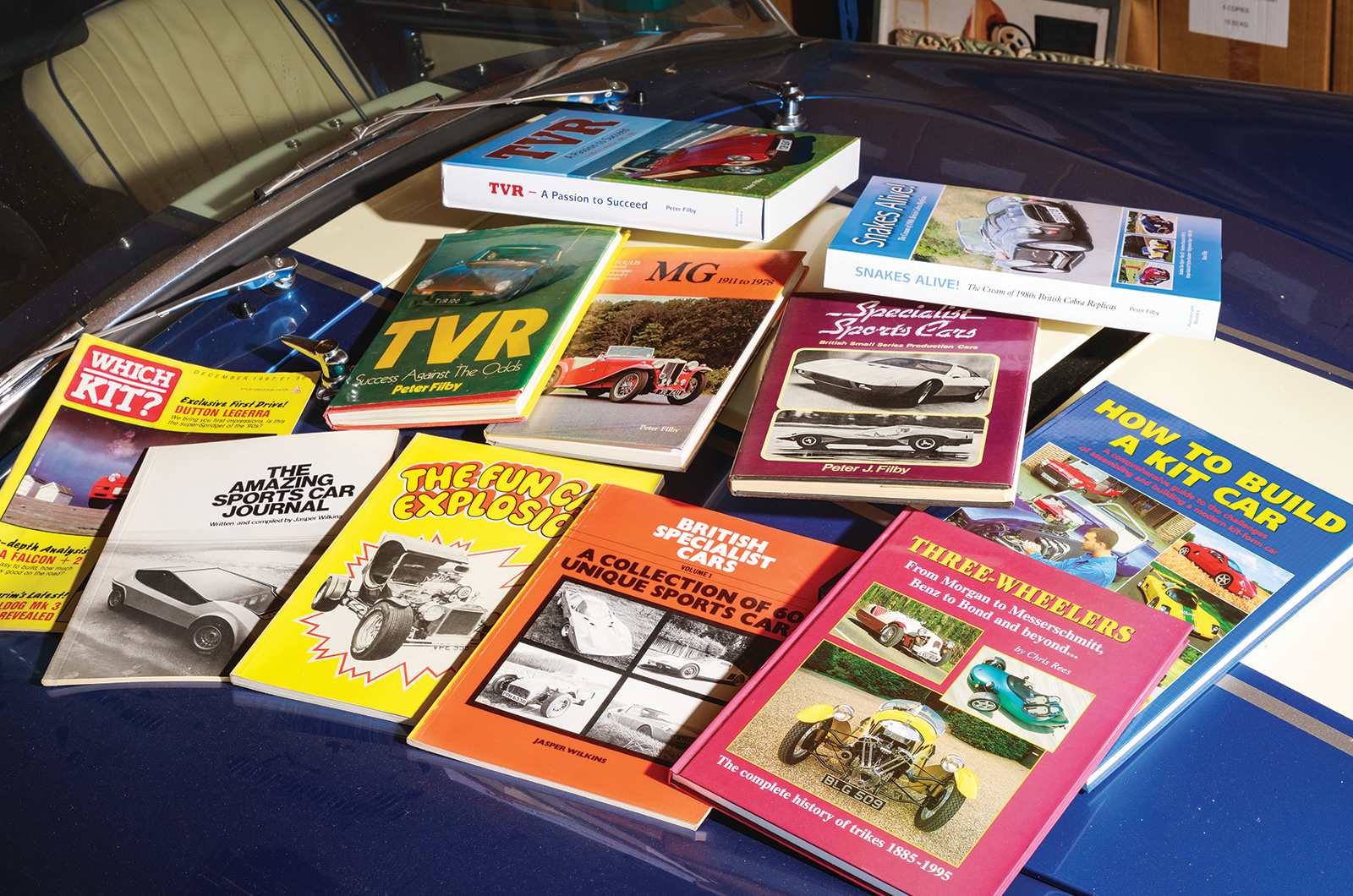

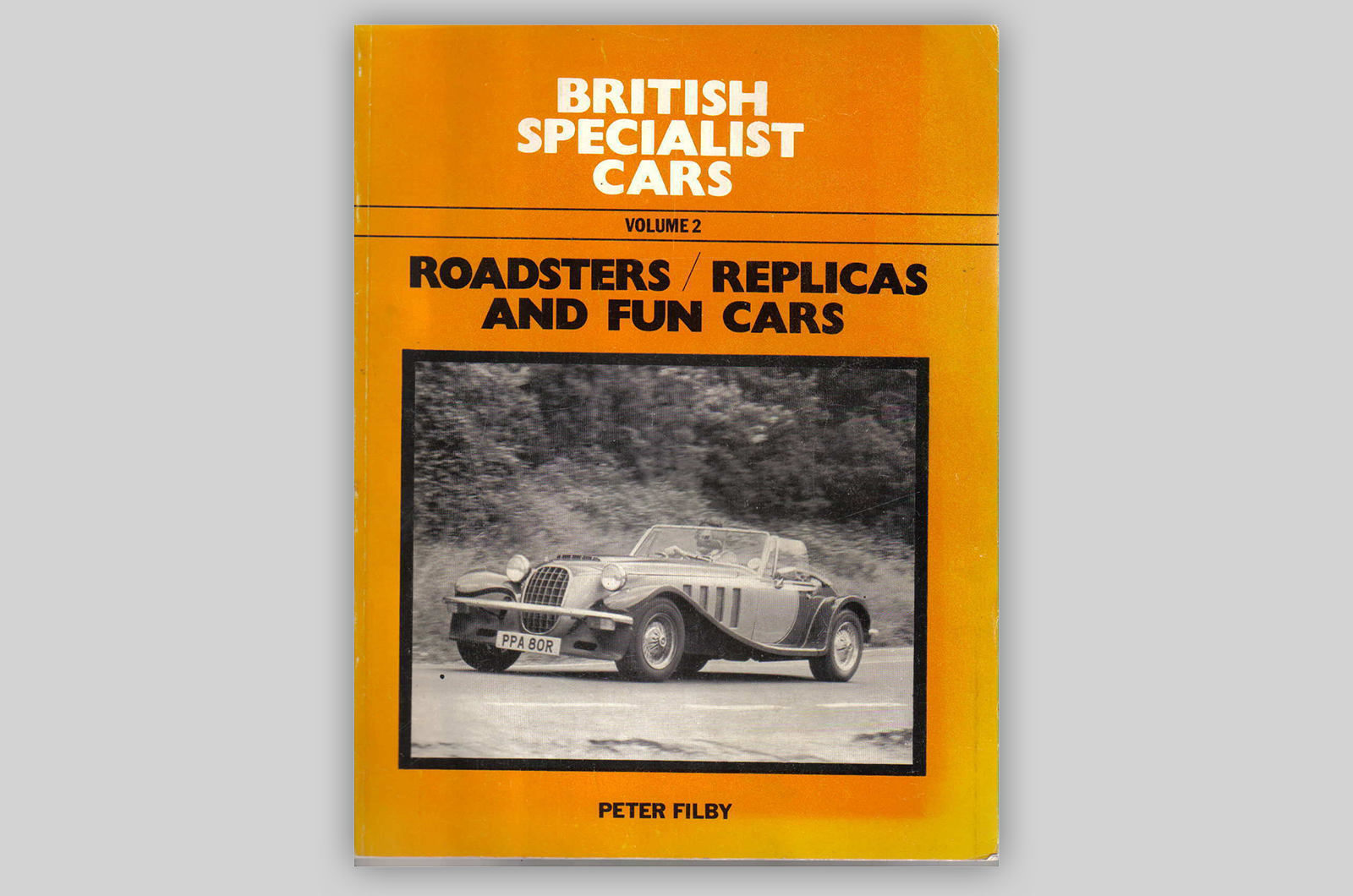

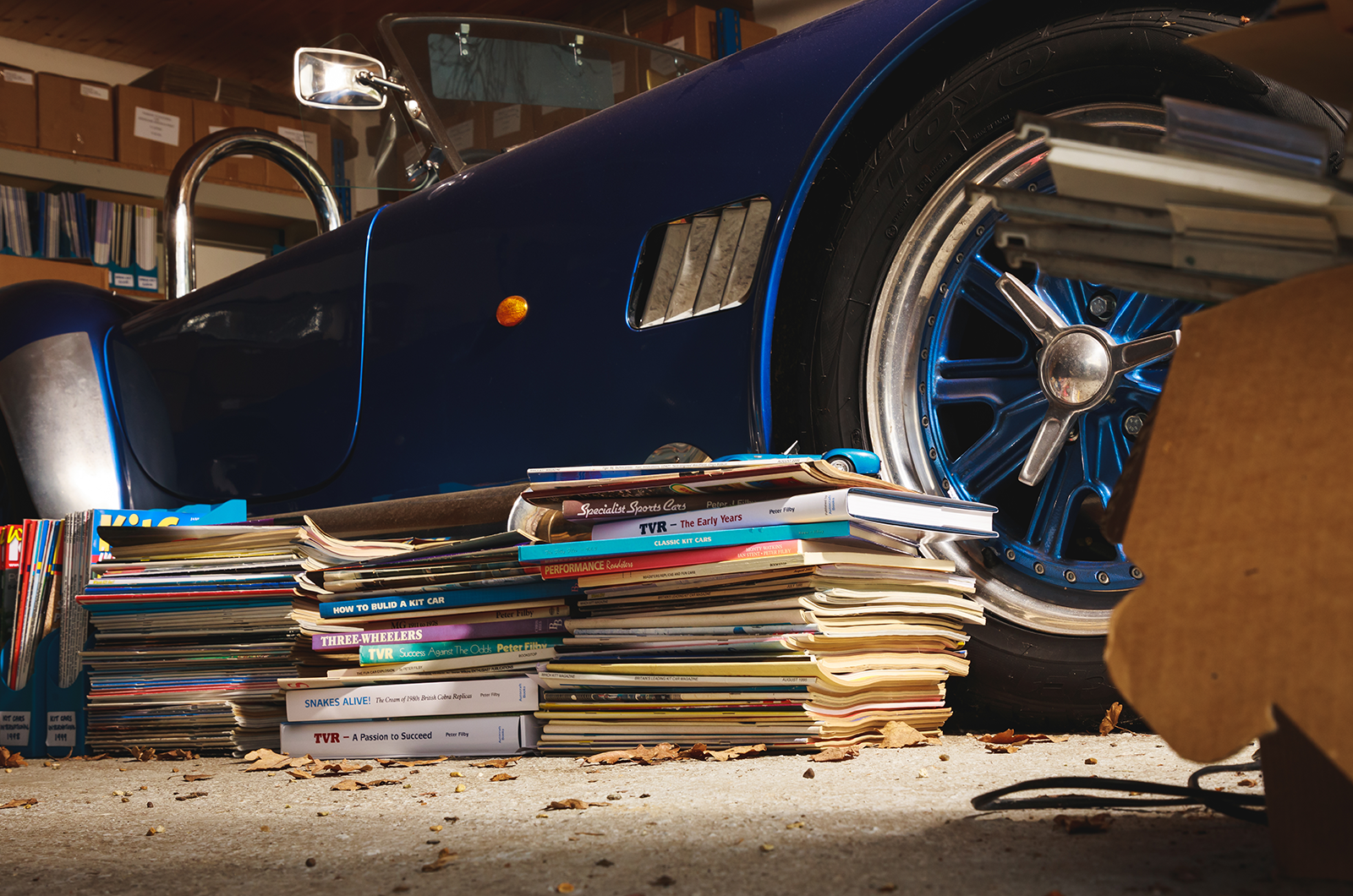

The many books and one-off magazines Filby produced during the UK specialist car boom hid another attempt to broaden out into the mainstream.

Called Carrera, it was an automotive lifestyle magazine that landed just before GQ but, if the boom in mens’ magazines that followed is any barometer – not to mention motoring titles such as Max Power tapping into broader culture – perhaps 1987 was just a handful of years too soon.

No matter in the long run, however. Which Kit?’s loyal following, with revenue bolstered by books and a busy calendar of British kit-car events, carried Peter’s small empire into the new millennium.

Boxes of books and magazines – and a Cobra replica – fill Peter’s garage

Even as SVA became Individual Vehicle Approval, further ratcheting up legislation and acting as a brake on the industry, his support was undimmed – right up until the moment he sold up in 2012. The title is now reimagined as Complete Kit Car magazine, with new owner Performance Publishing.

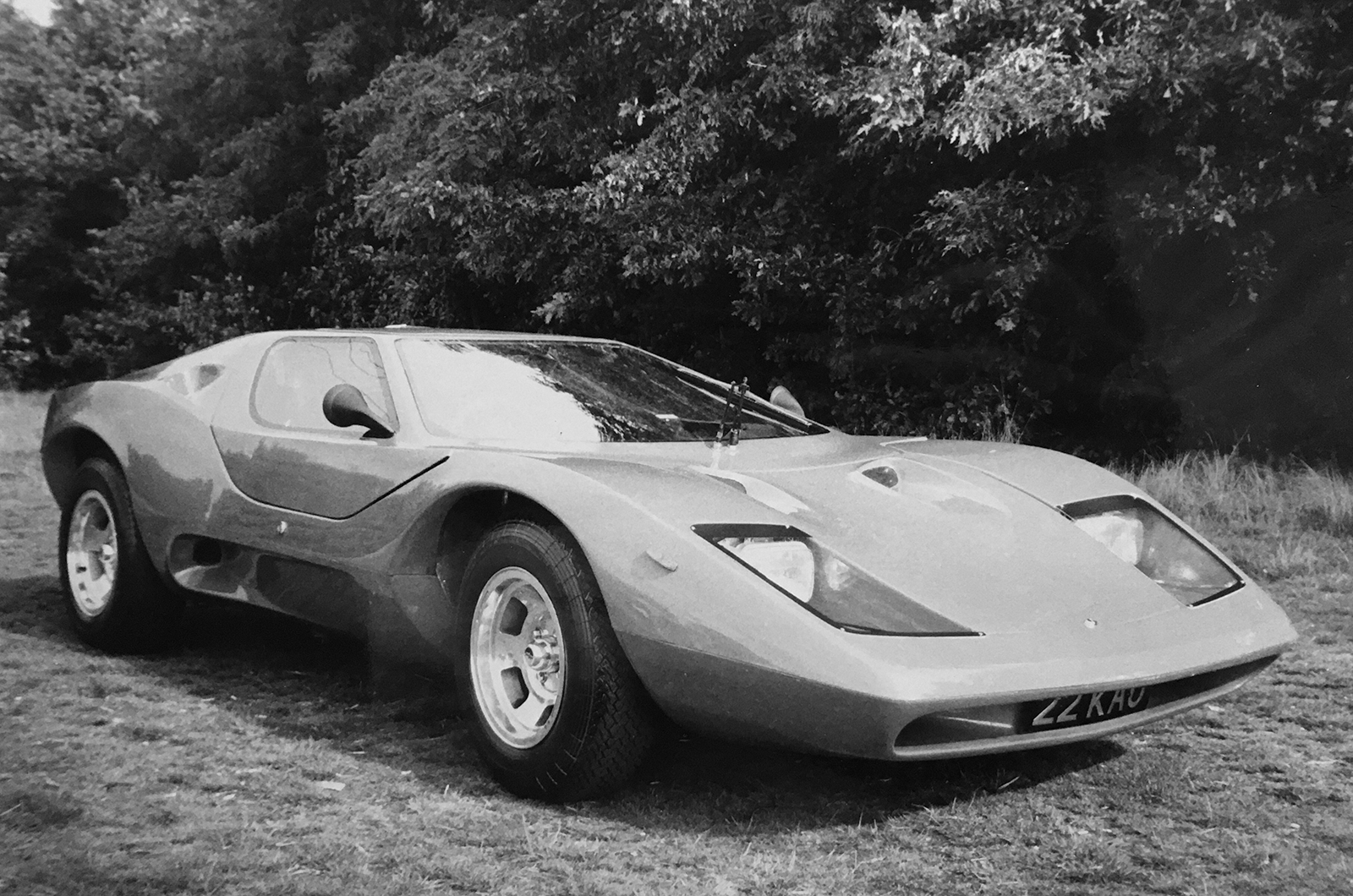

At his home, as Peter puts away those boxes of books and pulls closed the garage doors, we grab our coffee cups and walk past what looks like a wedge-shaped Mini Moke under a car port.

It’s a Siva Mule: an open, Mini-based buggy originally made in the early 1970s – and the polar opposite of the immaculate Cobra replica tucked away from the elements on the other side of the garage wall.

Peter Filby in his garage, surrounded by those things that mean the most to him

“It’s a fun little thing that we used to keep at the offices in Reigate,” Peter laughs. “We’d use it for sandwich runs and to pop to the Post Office.”

It seems symbolic. Only 12 were made and, unfairly or otherwise, it might well be lost to the world but for the shelter of Peter’s lean-to.

It’s fair to say the kit-car industry owes a similar debt to this man and his varied adventures in specialist automotive publishing.

Images: Max Edleston/Performance Publishing

Thanks to: Performance Publishing

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

Something Special: the quirky world of low-volume British classics

Children of the revolution: Deep Sanderson DS301 vs Ogle SX1000 vs Mini Jem vs Unipower GT

Lotus Six: flyweight flyer

Montlhéry Midget vs Austin Seven Ulster TT